In April, the United States Supreme Court held in Williams-Yulee v. Florida Bar that a state may limit a judicial candidate or a judge’s right to personally solicit campaign funds.

The 5-4 majority opinion was written by Chief Justice Roberts, who emphasized the need to ensure the public’s perception of the integrity of the judicial system does not wane with the increasing costs of judicial campaigns.

In Williams-Yulee, the Court found that a state has a compelling interest in preserving public confidence in the integrity of its judiciary. The power of the court relies solely on the willingness of the populace to adhere to its decisions. The court has no way to persuade the public by either the purse, as in our legislative branch, nor by the sword, as in our executive branch. If the public’s perception is that a judge can be bought through campaign funding, that perception will erode the public’s confidence in the integrity of the court and will undermine our three-branch system of justice. The Court stressed the necessity of preserving public confidence by allowing states to keep the judge out of the campaign money fray. Williams-Yulee addresses the two-edged sword of public misperception when a judge personally asks for funds. The first side is the concern that a judge will favor donors in his or her judicial decisions; the second that donors may fear judicial retaliation if they do not contribute when asked for money by the judge.

For the judge or judicial candidate, raising money for elections can be fraught with ethical pitfalls and is open to easy misperception by the public regarding the influence donors have on the judge.

Though the Court only addressed the involvement of the judge in personally soliciting campaign funds, the discussion over the efficacy of judicial elections is being heard in every state. Campaigns cost money and judicial elections are becoming more and more expensive.

Currently, 39 states provide for some form of judicial election. These elections occur on both partisan and non-partisan ballots. Seven states elect their final appellate court (supreme court) justices in partisan elections. Many more states allow partisan ballots for trial court seats.1 But beyond the spending in judicial races by political parties, the largest increase of money raised was from special interest groups.2

The National Judicial College reached out to two judges for their thoughts on the impact of money, especially big money, in judicial elections. Our first viewpoint is from NJC alumni Justice Sue Bell Cobb (AL), who in 2006 was elected chief justice of Alabama and at the time ran the most expensive judicial campaign in U.S. history. She discusses the awkwardness and the pressures of raising campaign money. Our second viewpoint is from Justice James Nelson (MT), who was appointed to his supreme court seat in 1993 and retired in 2012. He discusses his view on “dark money” in judicial elections and its potential to change the way judges decide cases.

» See what money has been spent in your state’s judicial elections

Sue Bell Cobb, Former Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court

Judging, as we all know, is not a vocation for the faint of heart. Pressure comes in many forms: to uphold the highest standards of conduct, to solve legal puzzles of tremendous complexity and difficulty, and — above all — to dispense justice. At times, judges even face threats to their physical safety and that of their families. That is pressure of a sort no one enjoys (I know; my home was firebombed by a disgruntled litigant when I was a trial court judge), but as judges we persevere and do our duty to the law and the ideal of justice. From the time of Hammurabi down to Solomon and to the present day, it was ever thus. But a new kind of pressure that many judges face is more troubling than any of these traditional challenges: the pressure to raise vast sums of money to run campaigns in judicial elections that grow ever more expensive.

And here too, I speak from unpleasant experience. When I ran for chief justice of my state in 2006, it was the most expensive judicial election in U.S. history. I raised $2.6 million, much of it from lawyers and interests with issues likely to come before the court. I did so for one simple reason: I had to. If I wanted to be competitive in the election, I had to raise the money, and those were the only sources available to me.

Contrary to the headline the editors of one national publication applied to an article I wrote for them, I am not “ashamed” of anything I did in that campaign or while on the bench.3 I followed the rules. I never directly solicited a contribution, because I was uncomfortable doing so. And as a judge I dispensed impartial justice to the best of my ability, which is all any of us can do. But I will never forget the pressure this broken system placed on me. First the pressure to assemble the resources my campaign required. Although I never solicited a contribution, I spent hundreds of hours calling friends and lawyers I knew, starting conversations that my campaign committee would later steer toward one about money. Then, after my election, came the pressure to explain to the public that the ridiculous amounts of money my opponent and I had reassembled (he raised far more than I) did not prevent me from upholding the highest standards of judicial conduct. The difficulty of this challenge was brought home to me by my first interview following the election, when a reporter asked me not about my status as our state’s first female chief justice or my reform agenda, but rather the unseemly appearance of the fundraising arms race in which I had so recently been engaged.

And then finally, after I took office, there was the pressure to administer justice as if the whole ordeal of money and politics had never happened. This may have been the greatest pressure of all. I know that I turned my mind against any form of bias with all my strength, and never consciously let politics intrude on the judicial process. Unconsciously? Well, by definition, I’ll never know for sure about that. I do know that studies by academics are increasingly finding a statistical correlation between campaign spending and judicial decisions as more and more money floods into elections.

So what are judges to do until this broken system is fixed? At a minimum, we must scrupulously follow the rules in our states regarding campaigns and fundraising. Each of us should also ask ourselves the tough ethical questions that those rules leave open. Are we comfortable soliciting contributions from lawyers and parties likely to appear before us? If so, what is the cost to the public’s perception of our courts? And we should each do what we can, according to our individual circumstances and personal beliefs, to reduce the role of money and politics in our judicial elections.

Jim Nelson, Former Justice of the Montana Supreme Court

Current cosmological theory predicts that some 74% of the known universe is composed of a pervasive dark energy — an invisible substance that may ultimately accelerate the universe into expansive oblivion.4

Not unlike dark energy, dark money spawned by the 2010 Citizens United5 case has come to dominate the universe of judicial elections and, if left unchecked, may well drive our expectation of a fair, impartial and independent judiciary into extinction.

Dark money is a term used to describe “political spending by innocuously named groups whose own donors — the source of the money —

[are]

allowed to remain hidden.” The source of these funds include 501(c)(3) groups and social welfare organizations — which, though required to report the amount of money they spend on electioneering — either directly or through contributions to super-PACs — are not required to disclose the identities of their donors.6 The Citizens United Court determined that money is a form of political speech protected by the First Amendment and, basically, that dark money organizations and super-PACs could expend unlimited sums of money to influence elections.7 The Court stated, while money contributed directly to a campaign breeds quid pro quo corruption, money expended indirectly for or against a candidate does not carry with it a corruptive effect.8

In his dissent to the Citizens United opinion, Justice Stevens predicted that the floodgates of money released as a result of the Court’s decision, would ultimately compromise the integrity of judicial elections as well.9 The justice’s fears were well-founded. As reported by the Brennan Center for Justice, “[o]n Election Day 2010, for the first time in a generation, three state supreme court justices were swept out of office in a retention election when voters expressed anger over a single controversial decision on same sex marriage.” The voter’s anger was fueled by a special interest campaign which poured nearly a million dollars into Iowa to unseat the justices.10 Matters only worsened. Since 2010, dark money spenders have expended significant amounts of money — funneled through the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and special interest and partisan groups — to influence judicial elections in North Carolina, Alabama, Arkansas, Tennessee,11 and in Montana.12 The independent news organization, Mother Jones magazine, reports that donations to judicial candidates ballooned from some $83 million in the 1990s to $206 million in the 2000s. States affected included Texas, Alabama, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Mississippi, Louisiana, West Virginia, North Carolina and Florida.13

Non-Partisan groups that have studied influence that money has and is playing in judicial elections paint a bleak future for a fair, independent and impartial judiciary. A few super-spenders are maintaining a dominant role in judicial elections. Increasingly, state judicial elections are being characterized by costly TV ad campaigns, character attacks, misinformation, attacks on merit selection of judges, and pushes to roll back public financing of judicial races.14 Studies have shown the mega-spending actually influences judicial decision making in civil15 and in criminal cases.16

Thirty-nine states elect their judiciaries. While it might be argued that the answer to the influence of big money is merit selection, there are two problems: first, as noted above, the mega-spenders are attempting to roll back merit selection laws; and, second, the appointers, who typically include legislators, governors, and committees, are often also under the influence of dark money. Indeed, the likely only real solution to this corruption of all three branches of government is a constitutional amendment to require real campaign finance reform and to undo Citizens United.17

Will dark money ultimately annihilate our gold-standard of a fair, independent and impartial judiciary? If dark money keeps up its present exponential expansion, that result is likely. And, in the words of the dark money folks, you can take that to the bank!

This story appeared in the 2015-16 issue of Case in Point, the annual magazine of the National Judicial College.

- Partisan Election of Judges, Ballotpedia, verified as of May 13, 2015.

- Bannon, Alicia et al. The New Politics of Judicial Elections, 2011-12: How new waves of special interest spending raised the stakes of fair courts, Brennan Center for Justice, Oct. 2013.

- Bell Cobb, Sue, I Was Alabama’s Top Judge. I’m Ashamed by What I Had to Do to Get There. On The Bench: Politico online magazine, March/April 2015.

- See, Paul Davies, The Goldilocks Enigma: Why is the Universe Just Right for Life? A Mariner Book, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006, pp 120-126.

- Citizens United v. Federal Election Com’n, 558 U.S. 310, 130 S.Ct. 876, 175 L.Ed. 753 (2010).

- What is Dark Money?, last visited April 6, 2010.

- See, Citizens United, 130 S.Ct. at 900, 913.

- See, Citizens United, 130 S.Ct. at 908-910.

- See, Citizens United, 130 S.Ct. at 968.

- Brennan Center for Justice, The New Politics of Judicial Elections: 2009-2010, last visited April 6, 2015. (Hereafter, Brennan Center Report). [NJC NOTE: The three justices were David Baker, Michael Streit, and Chief Justice Marsha Ternus. Justice Ternus taught in the NJC’s course When Justice Fails: Threats to the Independence of the Judiciary, July 27-30, 2015, in Washington, D.C.]

- See, Koch Brothers and D.C. Conservatives Spending Big on Nonpartisan State Supreme Court Races, last visited April 6, 2015.

- See, James C. Nelson, It’s Time to Make a Change in Selecting Judges in a Post Citizens United World, Montana Lawyer, February 2015, p. 21, 26.

- See, How Dark Money Is Taking Over Judicial Elections, last visited April 7, 2015.

- See, Brennan Center Report.

- See, Joanna Shepherd, Justice at Risk, an Empirical Analysis of Campaign Contributions and Judicial Elections, last visited April 6, 2015.

- See, Joanna Shepherd and Michael S. Kang, Skewed Justice: Citizens United, Television Advertising and State Supreme Court Justices’ Decisions in Criminal Cases, last visited April 6, 2015.

- See, for example, the work being accomplished on this solution by Free Speech for People.org, last visited April 7, 2015.

RENO, NV (PNS) – As they eye their inaugural football season this fall, the Gaveliers have question marks...

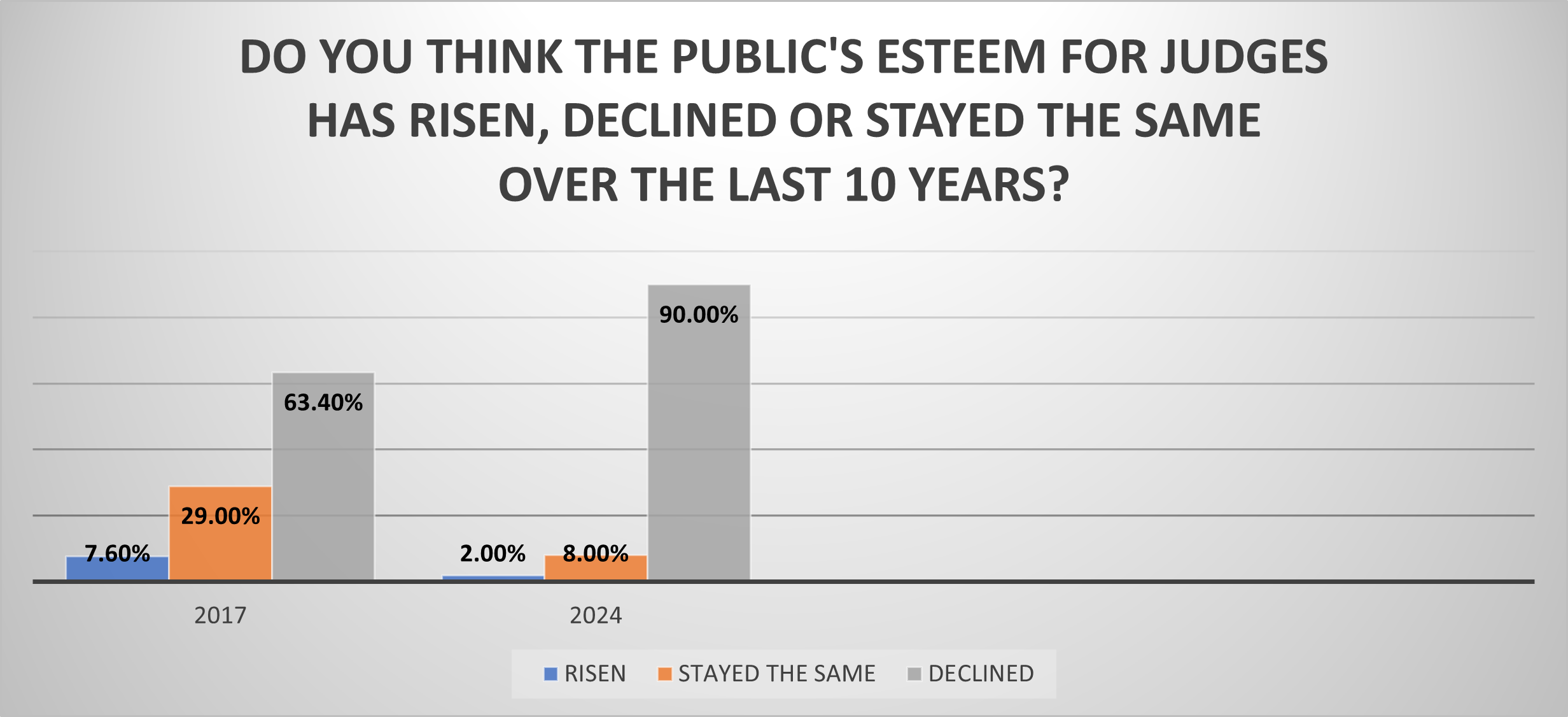

In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out of 10 judges believe the publi...

RENO, Nev. (Jan. 26, 2024) — The nation’s oldest, largest and most widely attended school for judges �...

RENO, Nev. (Feb. 7, 2024) — National Judicial College President & CEO Benes Z. Aldana received the Am...

It’s the bear, by a clear majority. A bear to be called Bearister. January’s Question of the Month* ...