“Domestic Violence, Developing Brains and the Lifespan: New Knowledge from Neuroscience”

In 2000 I added a ground breaking unit on the neurobiology of trauma to the National Judicial Education Program’s (NJEP) curriculum Understanding Sexual Violence: The Judicial Response to Stranger and Nonstranger Rape and Sexual Assault. This “hard science” knowledge from neuroscience did not exist when I wrote the first version of that curriculum in the mid-1990s. Judges have found this neuroscience unit extremely helpful in understanding phenomena such as why the way in which traumatic memories are recorded and recalled prevents trauma victims from producing the sequential, never-forget-a-detail narrative that most people wrongly expect.

Today we are at a comparable knowledge–development point with respect to the neuroscience on the impact of domestic violence on children, which I have explored in an article for The Judges’ Journal titled “Domestic Violence, Developing Brains and the Lifespan: New Knowledge from Neuroscience” . With the advent of magnetic resonance imaging, neuroscientists have produced scores of studies documenting on a neuronal level both the profoundly negative impact of exposure to domestic violence on children, and how children can recover when they are safe and secure in the care of their non-abusing, primary caregiver parent, who is usually their mother. The children sampled for the 2011 Office of Justice Programs survey “Children’s Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence and Other Family Violence” reported that 78% of intimate partner violence incidents and 88% of the most severe incidents were perpetrated by males.

Neuroscience Findings on the Impact of Domestic Violence on Children

The vast social science literature on the impact of children’s exposure to domestic violence is now confirmed and explained by neuroscience. A review of more than 1,000 social science articles about the behaviors seen in children exposed to domestic violence concluded:

At its most basic level, living with the abuse of their mother is to be considered a form of emotional abuse, with negative implications for children’s emotional and mental health and future relationships…. Growing up in an abusive home can critically jeopardize the developmental progress and personal ability of children, the cumulative effect of which may be carried into adulthood and can contribute significantly to the cycle of adversity and violence.

This conclusion is supported in an article by nine neuroscientists, pediatricians, physicians, and public health experts titled, “The Enduring Effects of Abuse and Related Adverse Experiences in Childhood: A Convergence of Evidence from Neurobiology and Epidemiology.” The authors assessed the findings of the long-running Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study in the context of the new knowledge from neuroscience. The ACE questionnaire includes questions about childhood exposure to domestic violence and adult perpetration After reviewing more than 17,000 responses from the mostly white, well-educated sample the authors wrote:

[T]he detrimental effects of traumatic stress on developing neural networks and on the neuroendocrine systems that regulate them have until recently remained hidden even to the eyes of most neuroscientists…..

The convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology calls for an integrated perspective on the origins of health and social problems through the lifespan.

A New England Journal of Medicine article, “Silent Victims – An Epidemic of Childhood Exposure to Domestic Violence” stated:

Childhood IPV [Intimate Partner Violence] exposure has been repeatedly linked to higher rates of myriad physical health problems in children…… Highly stressful environmental exposure, such as exposure to IPV, causes children to repeatedly mount the ‘fight or flight’ reaction, [resulting in the] biologic embedding of stress.

Implications for Judges of the New Knowledge from Neuroscience

The evolution of our understanding of the impact of domestic violence on children’s brains and the implications for the courts is captured in a short video, First Impressions: Exposure to Violence and a Child’s Developing Brain, featuring Dr. Bruce Perry, Senior Fellow of the ChildTrauma Academy in Houston, Texas and Dr. Linda Chamberlain, Founding Director of the Alaska Family Violence Prevention Project. Dr. Perry explains that contrary to what was long believed, neuroscience shows that the brains of babies and young children are sponges that soak up and are shaped by everything in their environment, including the harm of exposure to domestic violence. Dr. Chamberlain explains the evolution of her understanding that even babies and young children are impacted by exposure to domestic violence, and how that impact is experienced and expressed by children of different ages.

As with the neurobiology of trauma unit in NJEP’s sexual violence curriculum noted above, judges and allied professionals attending programs where the information in “Domestic Violence, Developing Brains, and the Lifespan: New Knowledge from Neuroscience” was discussed found it very useful. After court programs for New York State judges and attorneys for children the organizer stated:

[M]any attorneys and parents involved in DV cases have questioned or underestimated the impact of domestic violence on children who are not directly involved in a domestic violence incident. Your article clearly outlines the neurological damage that can happen to a child’s brain who is exposed to domestic violence. This information greatly supports the safety concerns for children that the judges have in many of these cases and further supports the responses that are imposed by the courts to protect children in these cases.

The justice system’s efforts to address domestic violence have been hampered by a schema that defines domestic violence as fist-in-the-face physical assault, and harm to children as possible only if they see it. But domestic violence has many dimensions, including coercive control, that together create an on-going climate of tension and fear. The knowledge from neuroscience leaves no doubt that when a non-abusing parent seeks help from the courts to protect her child, judges’ decisions can literally shape the child’s brain and impact the child’s mental and physical health, learning capacity and behavior, across the child’s lifespan. The most beneficial actions a judge can take for children exposed to domestic violence are to support their nurturing relationship with their non-abusing parent, which is inextricably entwined with that parent’s safety, and to protect the child from future exposure to violence, even if that requires closely supervising or even eliminating the abusing parent’s time with the child. And note that even in situations where factors such as poverty, fear, and cultural/religious norms prevent the abused parent from leaving, removing children from the protective parent with whom they are bonded creates its own trauma for the child.

Neuroscience has now provided us with much needed information about the impact of domestic violence on children at, literally, the neuronal level. I hope that learning about this “hard science” will help judges understand why awarding custody, joint custody, or unsupervised visitation to an abuser can be so damaging for children.

© Lynn Hecht Schafran, 2016

RENO, NV (PNS) – As they eye their inaugural football season this fall, the Gaveliers have question marks...

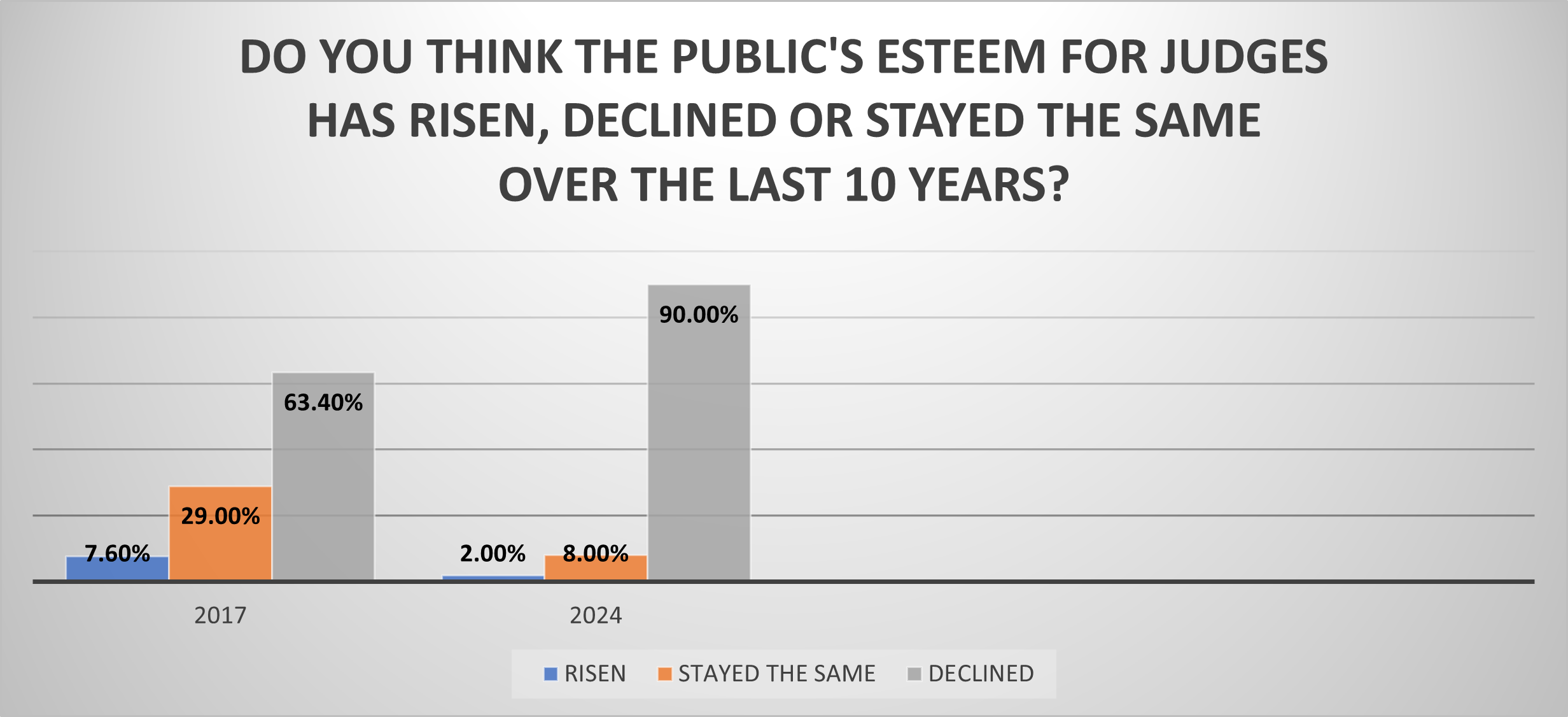

In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out of 10 judges believe the publi...

RENO, Nev. (Jan. 26, 2024) — The nation’s oldest, largest and most widely attended school for judges �...

RENO, Nev. (Feb. 7, 2024) — National Judicial College President & CEO Benes Z. Aldana received the Am...

It’s the bear, by a clear majority. A bear to be called Bearister. January’s Question of the Month* ...