As a longtime judicial officer, I was excited to be summoned for jury duty in January 2017. When I arrived at the jury assembly room, I wondered why there were so few potential jurors. The jury commissioner explained: There was only one trial set that day, a criminal case.

I was called in with the first batch of potential jurors and followed the bailiff to the third floor of the courthouse. I knew the assigned judge; her courtroom was across the hall from the chambers I occupied until my retirement in November 2015. Sitting in that hallway was a bit unsettling.

The bailiff announced the names of the first potential jurors and they took seats in the jury box. I was not part of that original group. Our group entered the courtroom, sat in the gallery, and waited to be called as possible replacements. The judge began by announcing the name of the case and the names of the lawyers and witnesses.

I knew them all.

That was because this criminal case derived from the worst child-abuse case I handled in 34 years on the bench. During my final 18 months on the juvenile court bench, I presided over seven different evidentiary hearings related to the abuse of this same child. At the end, I presided over the adoption.

As I recalled the photographs and testimony of the abuse, I began to shake uncontrollably. I felt sick to my stomach. I had trouble breathing normally.

The judge was asking whether any of the jurors already seated knew anyone involved in the case and if the expected two-week trial duration would cause an undue hardship. Many had reasons to be excused, so within a few minutes the clerk called my name as a replacement. I immediately asked to approach the bench and explained to the judge and attorneys that I could not sit as a juror because of my involvement with the earlier cases. Of course, I was excused.

That might have been the end of it, but it wasn’t.

I went back to the jury meeting room and got my official discharge from service. It took 15 minutes for me to stop shaking and feel strong enough to leave the courthouse. I went to my favorite coffee shop, got a cup of tea, and began to process what had happened to me.

As presiding judge of the Pima County Juvenile Court, I had led the effort to transform our court into a trauma-responsive one. I required everyone working at the court to learn about vicarious trauma before they were trained about the trauma affecting our consumers. So how could I have been so affected by something that had happened two years earlier? I did this work for more than three decades without flinching. It wasn’t that the work didn’t affect me; it profoundly affected me. But I had taught myself how to manage it.

Or so I thought before reporting for jury duty that day.

Vicarious trauma is real. It can affect anyone who encounters those who have suffered trauma of any kind, from auto accidents to child abuse to serious medical conditions. Law enforcement officers, doctors, nurses, child-welfare investigators, firefighters, and other first responders are the most obvious potential victims of vicarious trauma.

What isn’t so obvious is what happens when, day after day and case after case, a judge is required to hear about terrible things that happen to people but cannot respond physically or emotionally in a naturally human way.

However horrific the testimony and exhibits, a judge must remain dignified, calm, respectful. Emotions must be buried. The victim in the child-abuse case had such severe injuries that the first doctor who examined her at the emergency room thought she had been born with birth defects. The police officer who found the child, minutes from death, choked up while testifying.

Remaining stoic in the midst of this much trauma was incredibly difficult, but I did it. At a steep cost.

Suppressing emotions for days, months and years carries a heavy toll. A kind of numbness can develop. Sleeping and eating suffer. Some people develop substance abuse or addictive exercise regimens. By the time I left the bench, I rarely cried or was visibly upset by anything that happened in my personal life.

Vicarious trauma can happen to any judge on any bench. Every day, people come to court to have judges solve problems they cannot or should not solve themselves: landlord-tenant disputes, child-support collection, custody and visitation disputes, elder abuse. In the child-abuse criminal case to which I was called for jury duty, that judge is going to have to hear the terrible evidence twice because a mistrial was declared two weeks into the trial.

When I began my judicial career at Tucson City Court in 1981, there was no training in how to avoid this kind of burnout. All day, every day, I listened to cases involving domestic violence, substance abuse, mental health issues. When I was appointed at Juvenile Court six years later, no one talked about how to handle the emotionally difficult caseload. For the first few weeks I cried every night.

Once, a prospective adoptive mother returned to court with the 6-year-old child and his tiny suitcase. She had told him he was going to visit his sister after the hearing. Instead, she relinquished him back to the child welfare agency. I was both angry and incredibly sad. When I knew I was going to cry, I left the bench to compose myself.

Three children on my delinquency caseload committed suicide. Others were murdered. I attended all of their funerals. I taught myself to maintain my composure in the courtroom.

I was a good judge; dignified, respectful and focused. I didn’t realize how this was affecting my emotional health.

Fortunately, things have changed. Over the past decade, judicial educators, including the National Judicial College, have offered conference and seminar sessions on reducing stress, enhancing judicial wellness, and recognizing and managing vicarious trauma. When offered as stand-alone sessions, these presentations are always the programs first to fill. Scores of online tools are available to help judges determine the extent to which work is affecting their physical and emotional health.

Most judges have now learned some basic techniques for managing judicial stress. Leave the courtroom on a regular basis. Take a break. A real break. Step outside, talk to a colleague, have a healthy snack, do yoga. When the sessions end and you return to your chambers, don’t let your assistant hand you a stack of phone messages or documents to sign. Very politely say that you are on a break and then take time for yourself. Except for emergencies, whatever needs your attention can wait.

These basic techniques may not be sufficient if a judge is experiencing vicarious trauma. It may be appropriate to talk with a medical or mental health professional. Vicarious trauma is not just judicial stress writ large.

Understand also that judges are not the only ones affected in a courthouse. When I observed a member of my courtroom team become very anxious during a case involving significant domestic violence, I asked privately whether there was a problem I could help with. I learned that this person had grown up in an abusive household and that listening to the testimony was very difficult. I loaned her a book from my collection of trauma resources.

I was fortunate that day I reported for jury duty because by then I knew quite a bit about trauma and vicarious trauma. That obviously didn’t immunize me, but it helped me understand what was happening. I now grasp why victims and witnesses sometimes struggle when having to re-live trauma through listening to descriptions or testifying about a traumatic event. I understand why trauma experts urge us to ask what happened to a person rather than what’s wrong with that person when evaluating troubling behavior.

The best part of the experience may have been realizing that my heart was working again.

RENO, NV (PNS) – As they eye their inaugural football season this fall, the Gaveliers have question marks...

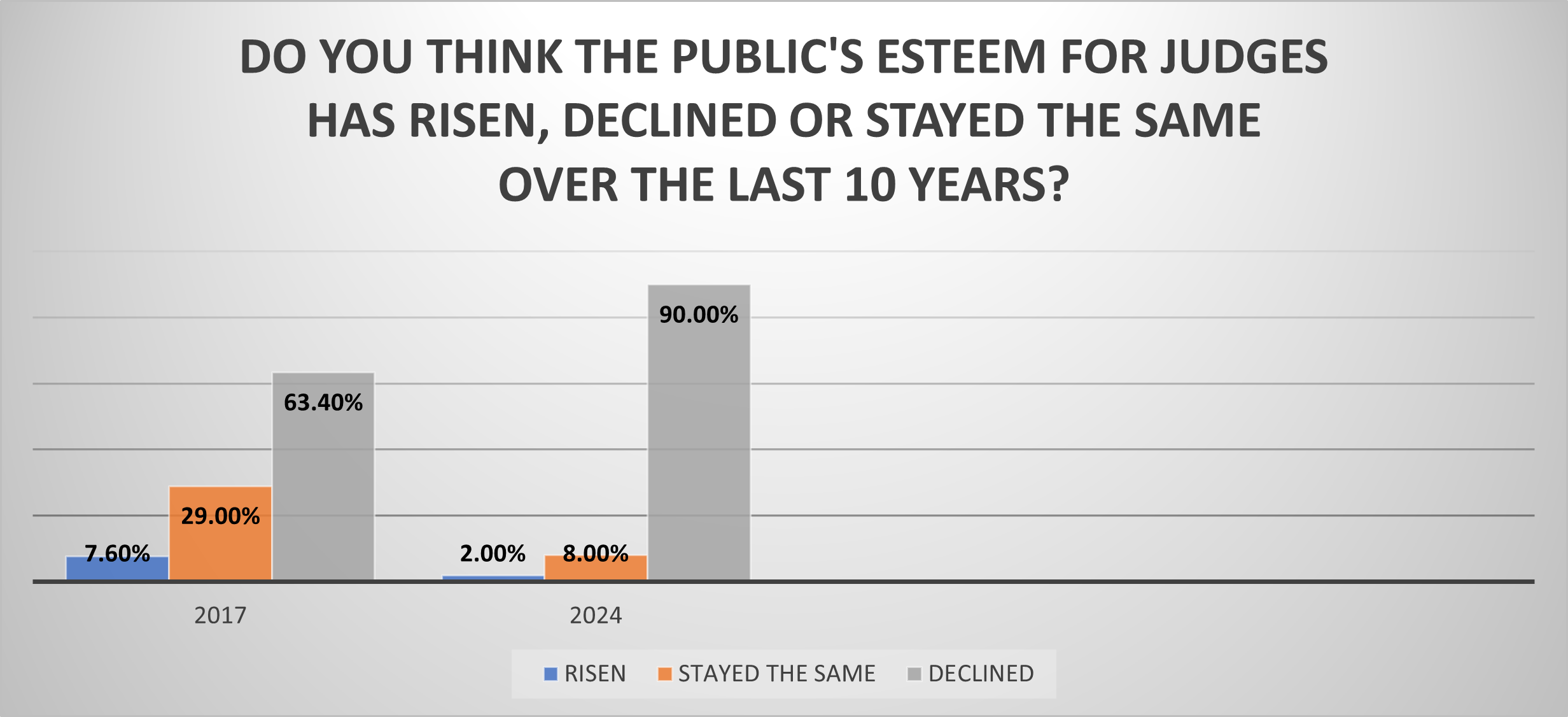

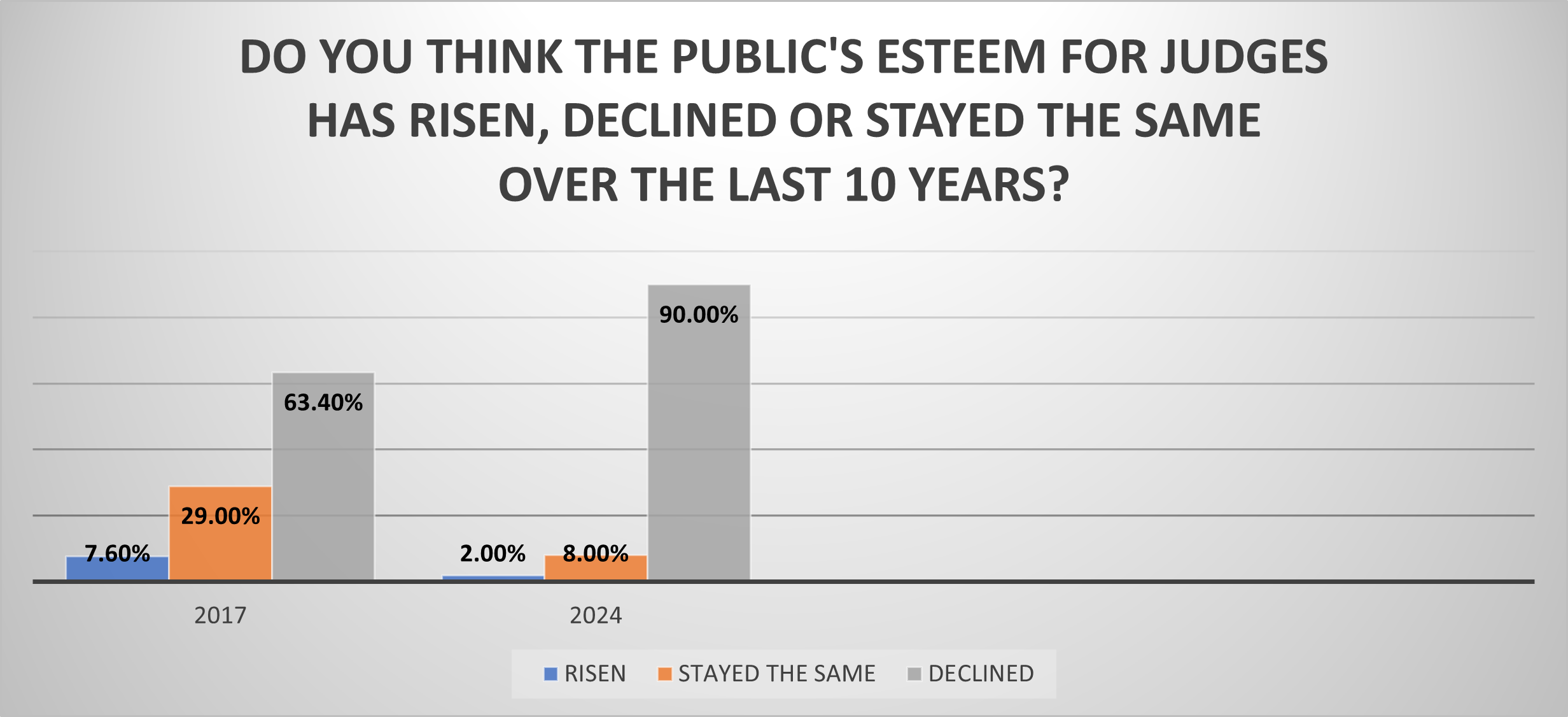

RENO, Nev. (March 8, 2024) — In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out...

In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out of 10 judges believe the publi...

RENO, Nev. (Jan. 26, 2024) — The nation’s oldest, largest and most widely attended school for judges �...

RENO, Nev. (Feb. 7, 2024) — National Judicial College President & CEO Benes Z. Aldana received the Am...