By Alisa Sparkia Moore, Esq., and Leryn Doggett Messori, M.A., PsyD Candidate

Whether and when a convicted defendant may be executed may depend on the level of his intellectual disability, age, and admitted evidence regarding mental illness, although the most relevant standards are not yet solidified.

Numerous challenges faced by lawyers, judges and defendants in recent cases “…bring together neuroscience and the law, where trying to explain the brain and human behavior can clash with how the legal system determines culpability, competency, and the manner in which such cases should be handled. Defense lawyers are increasingly introducing high-tech brain images and citing studies that link brain injury and violence to explain, excuse or mitigate criminal behavior” (Davis, 2012, para. 6).

The accepted evidentiary standards for challenging the imposition of an appropriate sentence, including the death penalty for a capital crime, for a defendant who may be “intellectually disabled,” vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. The issue is whether a person with severe mental retardation could form the mens rea (intent to commit an act) necessary to commit a crime, given the lack of mental capacity (i.e. Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951). And now, the question arises as to what evidence will best help the finder of fact reach that decision.

Age as a specific limitation on the use of the death penalty has been addressed recently. In Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005), the Supreme Court held that the execution of juveniles for crimes committed while under the age of 18 constituted “cruel and unusual punishment” prohibited by the Eighth Amendment, and acknowledged ‘a lack of maturity and an underdeveloped sense of responsibility’ in adolescents, as well as a national and international move away from applying the ultimate punishment.

In Penry v. Lynaugh, 362 U.S. 402 (1989) the Supreme Court held that a defendant in a capital case “must be permitted to present evidence of his intellectual disability” (p. 340). The Court fell short of adopting the “cruel and unusual punishment” or “national concensus against executing the mentally retarded” arguments raised by the defense, however (McCluskey, 2015).

But in Atkins v. Virginia 536 U.S. 304 (2002) the Court ruled that executing the intellectually disabled (then known as “mentally retarded”) is constitutionally prohibited. They classed it as a needless imposition of pain and suffering that amounts to “cruel and unusual punishment” because it fails to serve the reasonable penal goals of retribution or deterrence” (Rippon, 2012, para. 3), explaining “that the mentally retarded are less culpable than most defendants because of their disabilities in ‘reasoning, judgment, and the control of impulses’ (p. 306)” and … that a national consensus has developed that they should not be executed’ (McCluskey, 2015, pp. 23-24).

Atkins relied on the definitions from the American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR) and the DSM-IV. What the Court called ‘mental retardation’ is now called ‘intellectual disability’, the AAMR is now the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD), and a new DSM was published in 2013, changing the definition and diagnostic requirements for Intellectual disability. These changes indicate both the fluidity of this area of science and the need for the law to regularly reassess the standards used in relevant cases.

State laws often rely on the use of the IQ test level (usually varying from 65-70 or so), which the Supreme Court labeled “imprecise” in Hall v. Florida 572 U.S. ____ , 134 S.Ct. 1986, 1995 (2014). In Hall, the defendant was sentenced based on Florida’s use of IQ test scores. The Court acknowledged the use of medical experts and professional expertise in defining and diagnosing mental conditions at issue in a case (p. 1993) and held that the Florida court had “failed to give effect to the medical/mental health profession’s definition of intellectual disability in two ways” (p. 1995, as cited in McCluskey, p. 29).

The Hall decision may have huge ramifications in terms of appeals for those incarcerated and awaiting execution, “[a]ccording to one estimate, as many as 20% of the more than 3,100 people on death row in the United States may have some level of intellectual disability (R. Coyne and L. Entzeroth, Geo. J. Fighting Pov. 3, 40; 1996), as cited in Readon, 2014, para. 6). Those numbers have not changed much in 20 years; as of January 1, 2016 there were 2,943 death row inmates (Death Penalty Information Center).

In Atkins, the Court also engaged in an extensive discussion of the now-named American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) and the American Psychiatric Association (APA) definitions, then noting “clinical definitions of mental retardation require not only subaverage intellectual functioning, but also significant limitations in adaptive skills such as communication, self-care, and self-direction that became manifest before age 18” (p. 318). As yet, no Constitutional minimum standard for determining retardation has been established by the Court (McCluskey, 2015, p. 27).

The individual states were left to further define the mental retardation (now intellectual disability) (Atkins, p. 317). And they did, taking into consideration the language in Atkins, the AAIDD, the APA, the IQ standards, and various medical/psychological/psychiatric language distinctions. It is in the various aspects of this three-pronged Atkins test that neuroscience is useful now and will be even more useful to courts as the science is further refined and finessed.

The inability of experts to definitively establish a causal connection between intellectual disability and the inability to made proper choices, resulting in criminal activity, has impaired the universal acceptance of such testimony.

Simon Rippon, with the University of Oxford, maintains that “the law draws an arbitrary dividing line using an inaccurate proxy measure,” and so “[l]awyers, neuroscientists, psychologists and philosophers need to collaborate to develop more sophisticated ways of measuring blameworthiness and allotting punishments that will be less arbitrary, and considerably more just” (2012, par. 5, 6).

In Hall, the Court said that “[t]he legal determination of intellectual disability is distinct from a medical diagnosis, but it is informed by the medical community’s diagnostic framework…” (p. 2000).

Some recent results indicate the use of neuroscience is impacting the courtroom in favor of the defendant. “The use of neuroscience as a defense is different from that of a psychological defense, or an insanity plea, because the diagnoses depend on the physical makeup of or damage to the brain, not a psychiatric evaluation (Koehler, 2012, para. 6). The utilization of medical diagnostic testing and mental health history has resulted already in judicial decisions against the imposition of the death penalty.

In one, the “lawyers of Ronell Wilson were able to convince a [federal] judge [in New York] that he is a person of such a low intelligence that he can’t function in society, and therefore can’t be put to death” relying on the standards set out in Atkins and Hall and reviewing the defendant’s extensive mental health issues, as well as his IQ scores, which, however, were only once under 70 in the nine times he took the test (Balsamo and Long, 2016, para. 2).

New cases continue to be handed down that will further clarify the constitutionality of the execution of the intellectually disabled defendant. For instance, in Brumfield v. Cain (Slip Opinion No. 13-1433, 2015), a Louisiana death penalty case dealing with intellectual disability, the issue raised was whether a state court’s denial of an Atkins claim, “when the defendant has not had the opportunity or funds to develop the claim, a decision based on an unreasonable determination of the facts?” and the Court (Sotomayer for the majority) held:

The state court’s decision rested on its determination that Brumfield’s IQ score was not low enough to prove that he had subaverage intelligence and that Brumfield did not show that his adaptive skills were impaired. However, an IQ test has a margin of error that, if applied to the score in this case, would place Brumfield in the category of subaverage intelligence; therefore, the state court could not definitively preclude the possibility that Brumfield satisfied this criterion, and to hold otherwise was unreasonable. Additionally, the factual record presented … provided sufficient evidence to question Brumfield’s adaptive skills. Because Brumfield only needed to raise reasonable doubt regarding his intellectual capacity to be entitled to an evidentiary hearing, the state court’s decision that Brumfield did not meet that low threshold was unreasonable (Oyez, 2015).

While issues of racial bias, prosecutorial misconduct, ineffective assistance of counsel, post-conviction exonerations, political issues involved with the election of judges, and challenges to execution methods are additional reasons to err on the side of life in prison across the board, the issue of using scientific data regarding brain damage or injury to support not executing a defendant is moving towards at least a federal ruling. The states which continue to execute defendants with intellectual disabilities, like Georgia and Texas, may bring the issue to a head (Totonchi, 2015).

A psychologist who examined 14 inmates who are now on Texas’ death row — and two others who were subsequently executed — and found them intellectually competent enough to face the death penalty agreed on Thursday never to perform such evaluations again. Attorneys for the 14 inmates hope the agreement will help their clients, who they argue are mentally handicapped, to escape lethal injection (Grissom, 2011, para. 1).

These kinds of horrendous results may be one reason the American Psychiatric Association approved and repeatedly reaffirmed their call for a moratorium on capital punishment in the U.S. until it can be used “fairly and impartially in accord with the basic requirement of due process” (American Psychiatric Association, 2014, para. 1)

The move to replace the death penalty with life in prison without parole would avoid this evaluation altogether. “Thirty-three jurisdictions, including 30 states and the District of Columbia, the federal government and the U.S. military, have either formally eliminated the death penalty or have not carried out an execution in the last nine years” and “[n]ationwide, in the six-year period between 2010 and 2015, only 10 counties imposed six or more death sentences” (Death Penalty Report, 2015) (emphasis added). Seven have repealed the ultimate penalty since 2007 (Wolf and Johnson, 2015).

This movement to eliminate the death penalty as a punishment alternative is tied, at least in part, to a recognition that the execution of those suspected of severe intellectual disability, while the science is not exact, is in conflict with this nation’s use of ‘an eye for an eye’ punishment.

“Of the 28 people executed [in the U.S. in 2015], 75% were mentally impaired or disabled, experienced extreme childhood trauma and abuse, or were of questionable guilt. An examination of the 2015 cases that resulted in execution reveal a disturbing pattern: It’s frequently not just one impairment, such as a low IQ score, that defines these cases, but rather multiple forms of disability and impairment (Death Penalty Report).

Moving the decision not to execute based at least in part on neuroscientific evidence seems to be supported by current Supreme Court decisions and the American philosophy of the use of punishment. If a defendant cannot form the required mens rea to commit the crime, how does execution benefit the People in ways that incarceration will not, unless the point is not justice but rather vengeance.Related CourseScientific Evidence and Expert Testimony (JS 622), September 26 – 19, 2016 [Clearwater, FL]

REFERENCES

(2014, Nov. 19) Eighth Amendment: Hall v. Florida, 128 Harv. L. Rev. 271 retrieved from http://harvardlawreview.org/2014/11/hall-v-florida/

American Psychiatric Association (2014) Position statement on moratorium on capital punishment in the United States. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Press retrieved from Position-2014-Moratorium-Capital-Punishment.pdf

Balsamo, M. and Long, C. (2016, Mar. 20) NY Killer off Death Row as Definition of Disabled Gets Tweak, Associated Press and ABC News, retrieved from http://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/ny-killer-off-death-row-definition-disabled-tweak-37792073

“Brumfield v. Cain.” Oyez. Chicago-Kent College of Law at Illinois Tech, n.d. Apr 26, 2016. <https://www.oyez.org/cases/2014/13-1433>

(2015) Death Penalty Report, The Charles Hamilton Houston Institute For Race & Justice, Harvard Law School, retrieved from http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/documents/2015-CHHIRJ-Death-Penalty-Report.pdf

Davis, K., (2012, Nov. 01) Brain Trials: Neuroscience Is Taking a Stand in the Courtroom , American Bar Association Journal, retrieved from http://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/brain_trials_neuroscience_is_taking_a_stand_in_the_courtroom/

Death Penalty Information Center, retrieved from http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/intellectual-disability-and-death-penalty

Florsheim, L., (2014, May 14) How Texas Keeps Putting the Intellectually Disabled on Death row, New Republic, retrieved from https://newrepublic.com/article/117765/death-penalty-mentally-disabled-how-do-states-keep-doing-it

Grissom, B., (2011, Apr. 15) Texas Psychologist Punished in Death Penalty Cases, Texas Tribune, retrieved from https://www.texastribune.org/2011/04/15/texas-psychologist-punished-in-death-penalty-cases/

Koebler, J., (2012, Nov. 09) Criminal Minds: Use of Neuroscience as a Defense Skyrockets, retrieved from http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2012/11/09/criminal-minds-use-of-neuroscience-as-a-defense-skyrockets

McCluskey, J.D., (2015) CAPACITY FROM LEGAL, MENTAL HEALTH, AND NEUROSCIENCE PERSPECTIVES, (Master’s Thesis, Florida Gulf Coast University)

Reardon, S., (2014, Feb. 20) Debate on Who Is Smart Enough to be Executed, Nature Magazine, retrieved from http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/debate-on-who-is-smart-enough-to-be-executed/

Rippon, D., (2012, Mar. 7) Arbitrary Execution: why the Law Needs Help from Neuroscience, Psychology and Philosophy, (Blog) retrieved from http://blog.practicalethics.ox.ac.uk/2012/03/arbitrary-execution-why-the-law-needs-help-from-neuroscience-psychology-and-philosophy/

Rosen, J., (2007, Mar, 11) The Brain on the Stand, New York Times Magazine, retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/11/magazine/11Neurolaw.t.html?_r=0

Totonchi, S.J., (2015, Nov. 18) Five Things Wrong with Georgia’s Death Penalty, The Marshall Project, retrieved from https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/11/18/five-things-wrong-with-georgia-s-death-penalty#.JzVUEixWt

Wolf, R., and Johnson, K., (2015, Mar. updated Sept. 14, 2015) Courts, states put death penalty on life support, USA Today, retrieved from http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2015/09/14/death-penalty-execution-supreme-court-lethal-injection/32425015/

RENO, NV (PNS) – As they eye their inaugural football season this fall, the Gaveliers have question marks...

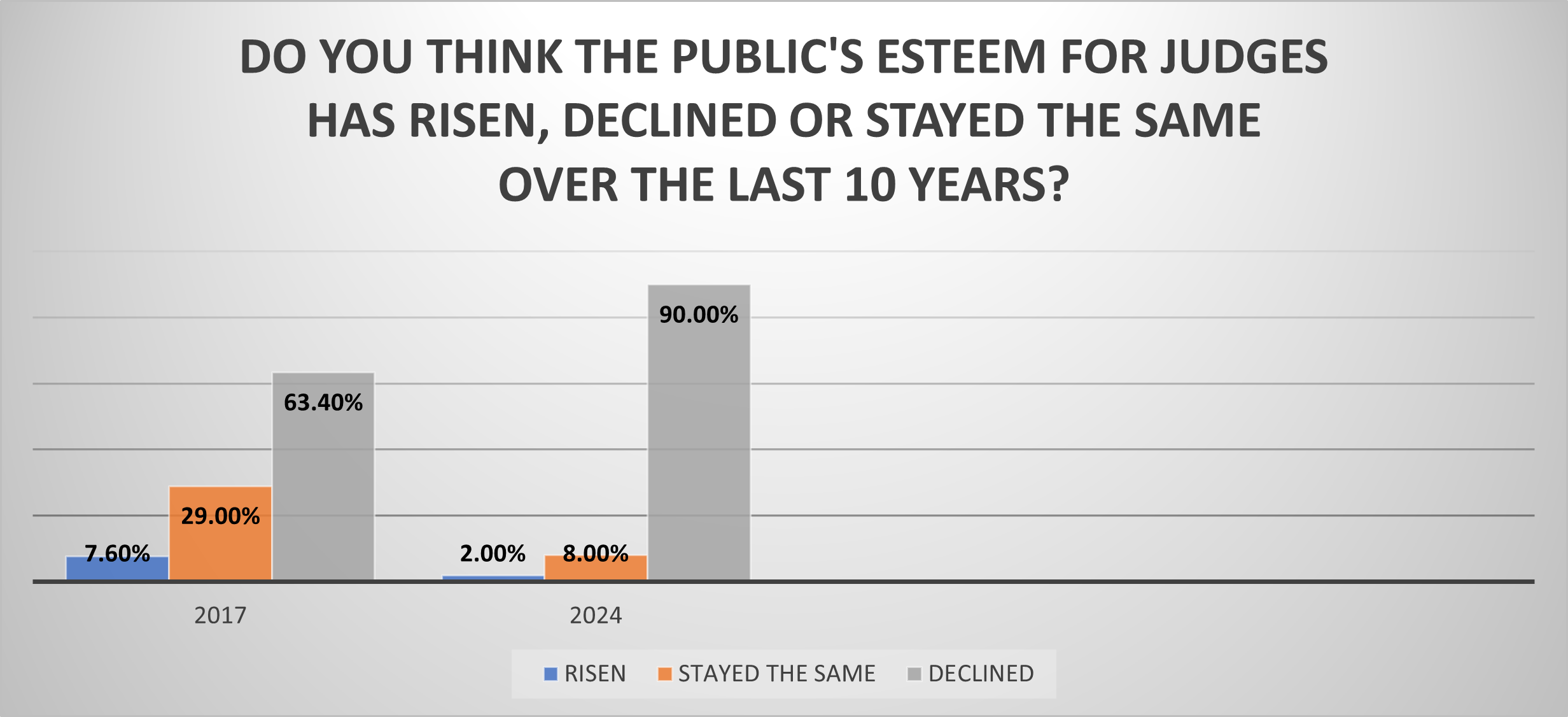

In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out of 10 judges believe the publi...

RENO, Nev. (Jan. 26, 2024) — The nation’s oldest, largest and most widely attended school for judges �...

RENO, Nev. (Feb. 7, 2024) — National Judicial College President & CEO Benes Z. Aldana received the Am...

It’s the bear, by a clear majority. A bear to be called Bearister. January’s Question of the Month* ...