NJC faculty members have many teaching tools at their disposal, but no teaching tool is more important than well-crafted learning objectives. A learning objective specifically states what the participant will be able to do after attending an educational session that he or she was unable to do prior to the session. While learning objectives must always be learner-centered, learning objectives also empower faculty members to tailor their presentations to a particular audience of learners.

Here are some examples of effective learning objectives:

At the end of this session, participants will be able to

- Identify special rules of admissibility used in relevancy analysis.

- Justify the exclusion of relevant evidence due to policy rules.

- Rule on the admissibility of out-of-court statements of witnesses and victims.

Learning objectives need to be clear and concise, achievable, and measurable. Learning objectives help the faculty member to decide what information is critical as opposed to information that is only nice to know.

Here are some examples of poorly constructed learning objectives:

At the end of this session, participants will be able to

- Understand the exclusion of relevant evidence due to policy rules. (The term “understand” is not measurable.)

- Learn the exclusion of relevant evidence due to policy rules. (The term “learn” is not measurable; neither are the terms “know” and “appreciate.”)

Faculty should use learning objectives to select learning activities and materials. Learning objectives should define the choice of learning activities. Likewise, material selection and creation should reinforce the learning objectives. Material that does not support a stated learning objective is either superfluous or just nice to know, and as such is not critical.

Learning objectives compel the faculty to adapt their presentation to match the time reserved for the session. Whether your session is scheduled for 40 minutes or four hours, you always have enough time to meeting your learning objective. This is true because you select your learning objectives based on the time allowed for your session. As a guideline, NJC faculty, delivering a 50-minute presentation, should not have more than three or four learning objectives.

The three parts of a well written learning objectives are:

- the opening statement “at the end of this session, the participant will be able to”;

- an observable verb such as identify, rule, or distinguish; and

- an appropriate conclusion to your sentence. For example, a learning objective addressing the admissibility of evidence would be “at the end of this session, the participant will be able to rule on the admissibility of out-of-court statements of witnesses and victims.”

In summary, learning objectives are learner-centered; they are not what the presenter will do, but rather what the learner will be able to do at the end of the session. They must be clear and concise, observable, and achievable in the time scheduled for the session. For a list of verbs, please download this PDF.

If you want assistance, the NJC’s academic staff are delighted to provide you with resources and assistance to help you compose learning objectives for your teaching.

Faculty Forum

News about and by NJC faculty members.

This month’s one-question survey* of NJC alumni asked, “How is 2024 shaping up for you and your court?�...

RENO, NV (PNS) – As they eye their inaugural football season this fall, the Gaveliers have question marks...

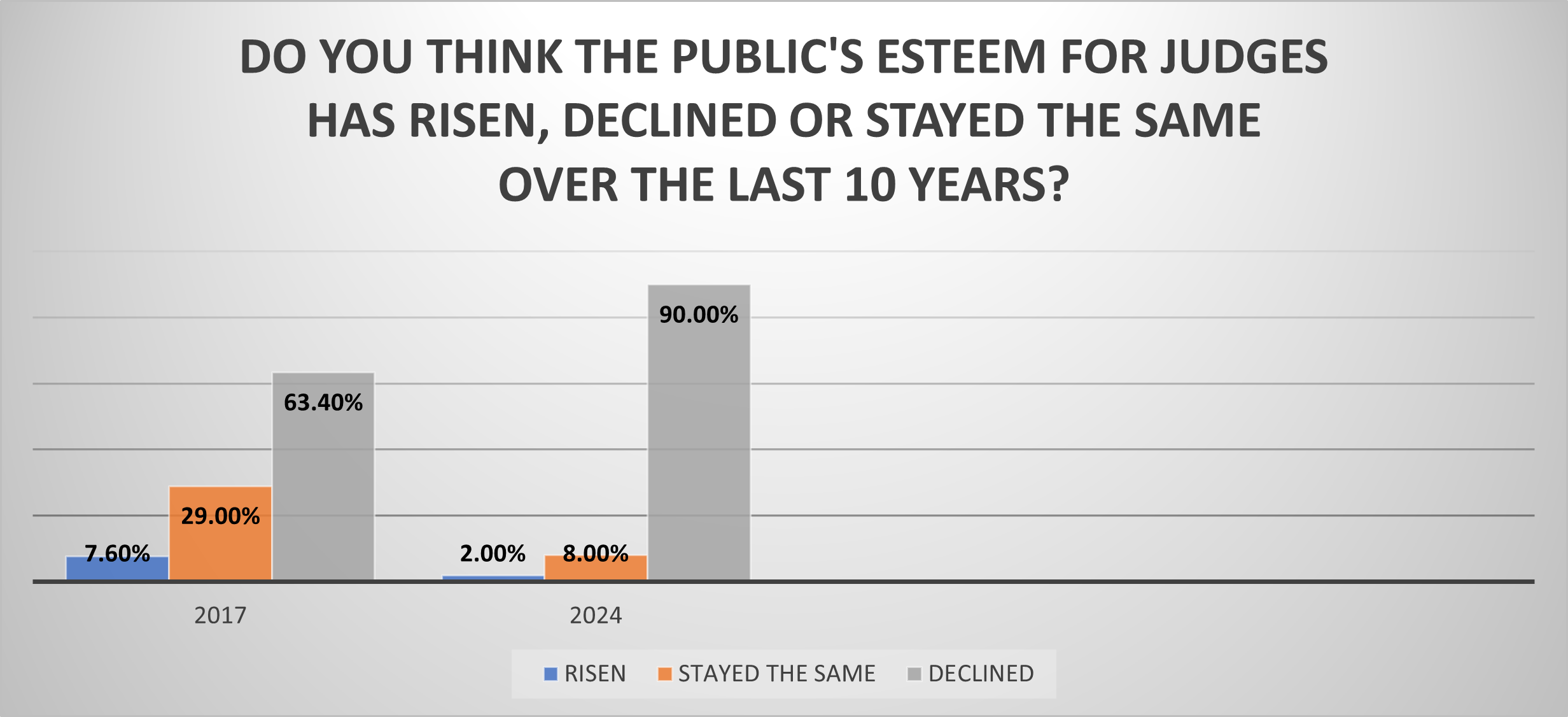

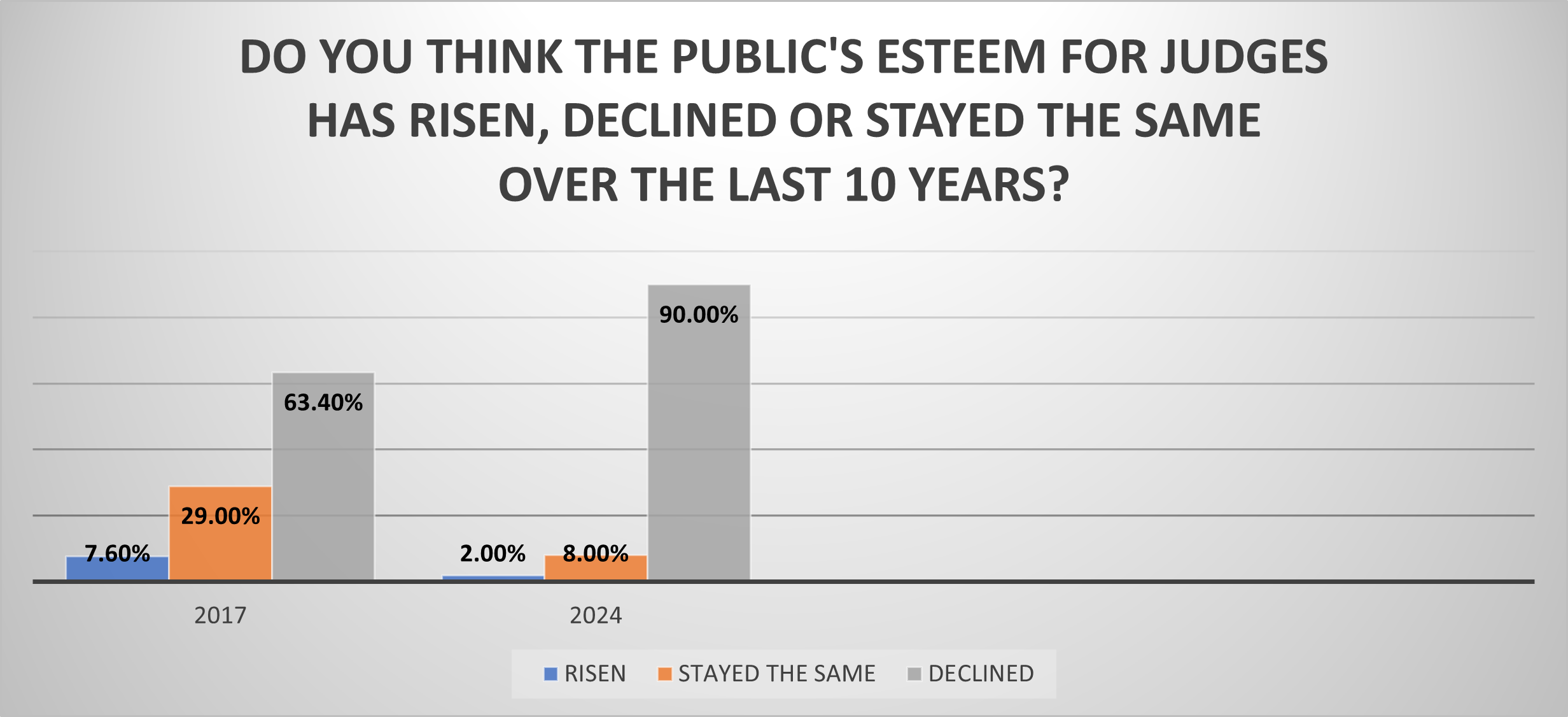

RENO, Nev. (March 8, 2024) — In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out...

In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out of 10 judges believe the publi...

RENO, Nev. (Jan. 26, 2024) — The nation’s oldest, largest and most widely attended school for judges �...