Military judges are experiencing the most comprehensive changes to the military justice system in the history of the Uniform Code of Military Justice. (Photo by Samuel Morse/Courtesy of the U.S. Air Force)

By Commander Paul Casey, U.S. Coast Guard

On January 1, a slew of changes to the Uniform Code of Military Justice took effect. They came from the recommendations of a group chartered by the secretary of defense in 2013. The revisions mainly align military justice with federal practices.

Here’s a summary of the major changes:

Criminal process

Before: Military judges were not involved with the criminal process until cases were set for trial (known as “referral”).

Now: They are involved, at least in terms of requests for pre-trial warrants, orders for electronic communications and the handling of ex-parte hearings with government counsel and the inevitable motions to quash subpoenas and challenges to warrant applications from litigators.

Jury size

Before: Juries could be set at any number above the minimum, which was five for serious crimes.

Now: The sizes of juries (“panels”) are fixed: four for misdemeanor level trials, eight for felonies and 12 for capital cases.

Alternate jurors

Before: Alternate jurors were not allowed to be seated with the jury. If a new juror was needed in the middle of a trial, the replacement had to be given time to read or listen to the trial transcript.

Now: As in the federal system, alternates can be seated with the primary jurors throughout the trial.

Sentencing

Before: Sentencing took place immediately after findings, although the final sentence would be completed by the jury in what looked like a separate sentencing trial.

Now: Although the accused always had the right to elect trial by military judge alone, the new law makes sentencing by the judge the default. Also, military judges will have to consider segmented sentences for each offense and decide whether sentences for confinement and fines will run concurrently or consecutively.

Although these changes have been universally welcomed by military justice practitioners, including judges, now comes the more difficult part: implementing the changes. Thankfully, each service continues to benefit from its Reserve judiciary units.

Many Reservist judges and judge advocates serve as assistant United States attorneys, Department of Justice staff attorneys, state court judges, and federal public defenders. They are well versed in the federal criminal procedures and will be a great help in the transition, along with the National Judicial College’s network of faculty and alumni.

RENO, NV (PNS) – As they eye their inaugural football season this fall, the Gaveliers have question marks...

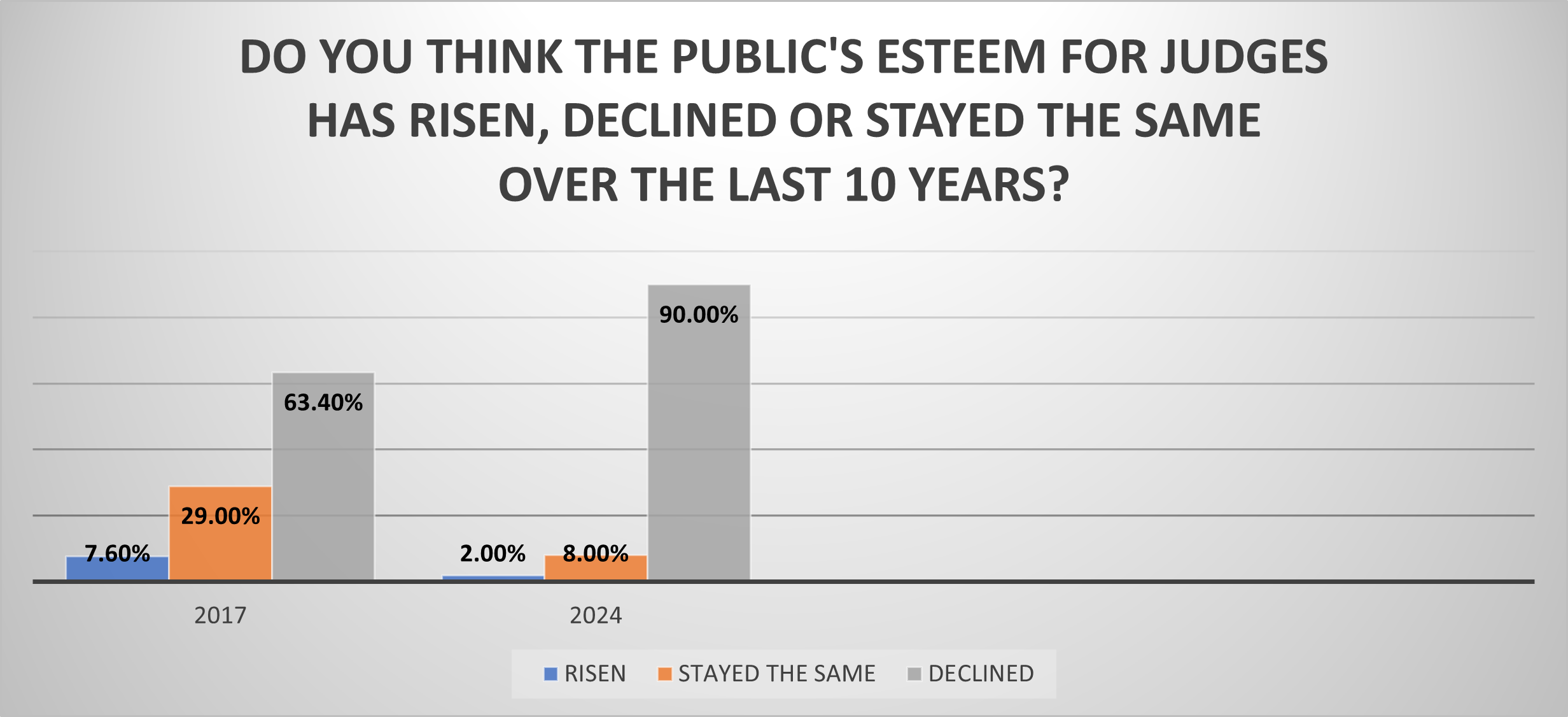

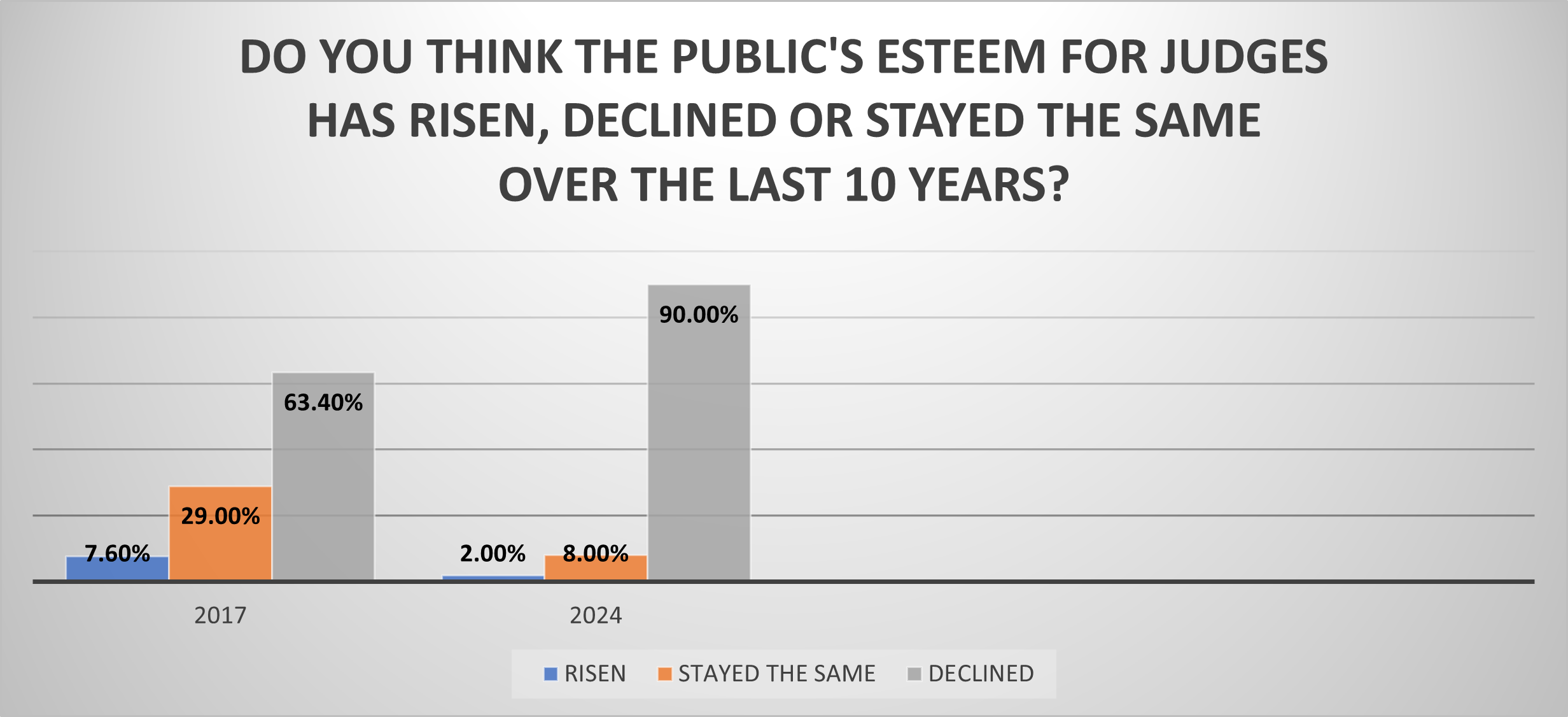

RENO, Nev. (March 8, 2024) — In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out...

In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out of 10 judges believe the publi...

RENO, Nev. (Jan. 26, 2024) — The nation’s oldest, largest and most widely attended school for judges �...

RENO, Nev. (Feb. 7, 2024) — National Judicial College President & CEO Benes Z. Aldana received the Am...