By Hon. Matthew W. Williams

Around the world, emerging democracies and post-conflict countries continue to look for ways to improve the functioning and credibility of their justice systems. Many First-World nations contribute the talent and experience of their judicial officers to these efforts. Not surprisingly, judicial officers within the United States are frequently sought by a diverse group of governmental organizations (GOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to consult with executive, legislative and judicial personnel in these developing nations. Judicial officers are frequently asked to assist in training advocates, prosecutors and judicial officers.

Receiving such an invitation is an incredible opportunity to contribute to a more stable world. It is also an incredible opportunity to learn and expand your own understanding of the function and processes of justice.

The range of GOs and NGOs in this work is immense. Examples of GOs include the U.S. State Department, the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Prosecutorial Development and Training, the European Union, and programs and projects directly sponsored by the government of a host country. NGOs include organizations funded by United States Agency for International Development (USAID), as well as the National Center for State Courts, the International Development Law Organization, the National Institute for Trial Advocacy, the American Bar Association Rule of Law Initiative, Justice Advocacy Africa, and The National Judicial College, just to name a few.

Some of these projects fully fund the judicial officer. Some projects are pure volun-tourism. Work in this area can include compensated contract work (the judicial officer is paid a stipend for their time and work, and the sponsoring organization pays all expenses). If you participate in such projects, don’t forget to comply with any reporting requirements from your local public disclosure commission! There are also projects for which judicial officers volunteer their time, but expenses are paid by the sponsoring organization. It can also include pure volun-tourism projects in which judicial officers donate their time AND pay their expenses. Here there may be tax-deduction opportunities.

No matter which type of program, the benefits of participating are immeasurable and incredibly satisfying.

Tips for success:

- Remember, whenever you are in another country you are subject to their laws.

The legal and physical protections that you take for granted in the United States may not exist. Activities that are accepted and legal in the United States may be subject to severe penalties in the host country. Spend some time researching the laws of the host country for your own protection. - Consider your travel documentation and travel medicine issues BEFORE accepting the assignment.

Each country has specific passport, visa and travel medicine issues that require advance preparation. Most countries require that your passport must be valid for 90 to 180 days AFTER you expect to depart. Some countries allow you to obtain a visa at the arrival airport, some require that you obtain it months in advance. Australia requires that you obtain a visa in advance, albeit through their easy-to-navigate online process. If you are going to an area where malaria is prevalent, you will want to start prophylactic medication BEFORE you arrive. Some countries require proof of a yellow fever vaccine before they will issue a visa. There is currently a shortage of that vaccine in the United States. Advance travel planning is crucial. The State Department website is a valuable starting place. - Don’t assume that you and the rest of your team are on the same page.

Work out your project plan BEFORE you depart. Getting into disagreements in front of your hosts is not only counterproductive but will embarrass your host organization. Be tolerant of different viewpoints, and recognize the jurisdictional diversity of your team. There is a common misperception around the world that the American justice system is one unified system. It is spread by the relative uniformity we see in federal court practice and by the fact that most attorneys practice within one court system or geographic area. In fact, the American system of justice consists of hundreds (if not thousands) of small, culturally specific justice systems, all of which operate under the umbrella of our Constitution. - Familiarize yourself with the governing provisions (constitution, statutes, rules, etc.) of the jurisdiction.

Don’t assume that they exist in English. - If you get the opportunity, observe the local justice system in action.

Your travel time may not allow much time for these preliminary meetings and observations, but they are invaluable.Recently I participated in training prosecutors in South America. As part of our preparation, we spent a morning in criminal court and then talked with the presiding judge. Initially we thought the calendar we were observing was a post-conviction review calendar. Many of the crimes had occurred three to six years previously. It seemed all of the defendants were either in custody or on a form of probation where they reported to their local police station each week. However, we eventually realized that we were observing a pre-trial case-management calendar. This realization struck home when one case came up in which the date of the crime was in 2007 (more than 10 years ago). For that entire time, the defendant had been reporting to his local police station every week and had been excluded from his home. The judge noted with some irritation that case had not yet been charged by the prosecutor. The judge instructed the prosecutor to get on that … which the prosecutor agreed to do but made no notes.Later we had a very frank discussion with the judge in which we learned about the evolution of the concepts of speedy trial and pre-trial probation/custody within that country. The judge noted that they had recently adopted an “English” model and anticipated cases would be tried within five years.Obviously, prosecutorial success rates on such trials are significantly less than jurisdictions in which trials occur closer to the crime. When we probed further, we learned that much of the delay came from the defense bar. It turned out that a criminal conviction precluded the defendant from obtaining a visa to leave the country, so it was worth it to many defendants to accept a lengthy period of pre-trial jail or probation in the hope of avoiding a conviction.This observation better helped us identify the transferrable skillsets we could offer in terms of trial practice and case management. It opened up a respectful dialogue on the needs of those stakeholders, which would not have occurred had we rushed in with “our” way of doing things.If you have a chance to observe or meet with local practitioners, take it! Ask questions. Take notes. “Why?” and “How?” are always good questions. Usually a question that begins with, “In the U.S. we …” is not going to be perceived as a question but a challenge. Learn first. Share later (but only after conscious thought). - Beware of your cultural and process assumptions.

Many of the processes, systems and best practices that work in the United States are culturally specific. They work because of a shared experience with our adversarial system of justice. Many justice systems around the world are based on an inquisitorial system of justice (think Italy). Just because the local system is different from the system within which you work, don’t assume you are there to transform it.When we look at the essence of what each process or procedure within ANY justice system is trying to accomplish, we quickly realize that all justice systems are basically trying to accomplish the same thing. There are just many different starting places and many ways to “skin the cat.” Just because they are different doesn’t mean they are wrong … they are just different.As an example, in 2014 I was working on an anticorruption training program for judges in Albania. Although the Albanian justice system is technically an adversarial system, it is steeped in generations of experience with an inquisitorial system. Many of the provisions of that system are also a reaction to the oppression and purges of the judiciary under the former communist leadership.The other U.S. consultant struggled with the fact that the foundation for the admission of exhibits and out-of -court declarations was not laid through the testimony of witnesses in open court. However, on closer examination the Albanian system uses a pre-trial process of authentication and validation that serves the same purpose. Once we understood that process, we were in a better position to identify transferable solutions, techniques and systems that could be discussed and taught to the advocates and judges.Another example: Leading questions are one of the cornerstones of our adversarial system of cross-examination. However, in many inquisitorial systems “suggestive questions” by the advocates are prohibited. Understanding the “why” of that prohibition in the context of the local system was important to develop a sustainable and transferrable questioning technique. - Go for it.

The opportunity to teach in an overseas program is one to be cherished. It gives you the opportunity to step outside the “water in which we swim” and see our system(s) of justice in a more objective light. You will learn far more than you teach. Good luck!

This month’s one-question survey* of NJC alumni asked, “How is 2024 shaping up for you and your court?�...

RENO, NV (PNS) – As they eye their inaugural football season this fall, the Gaveliers have question marks...

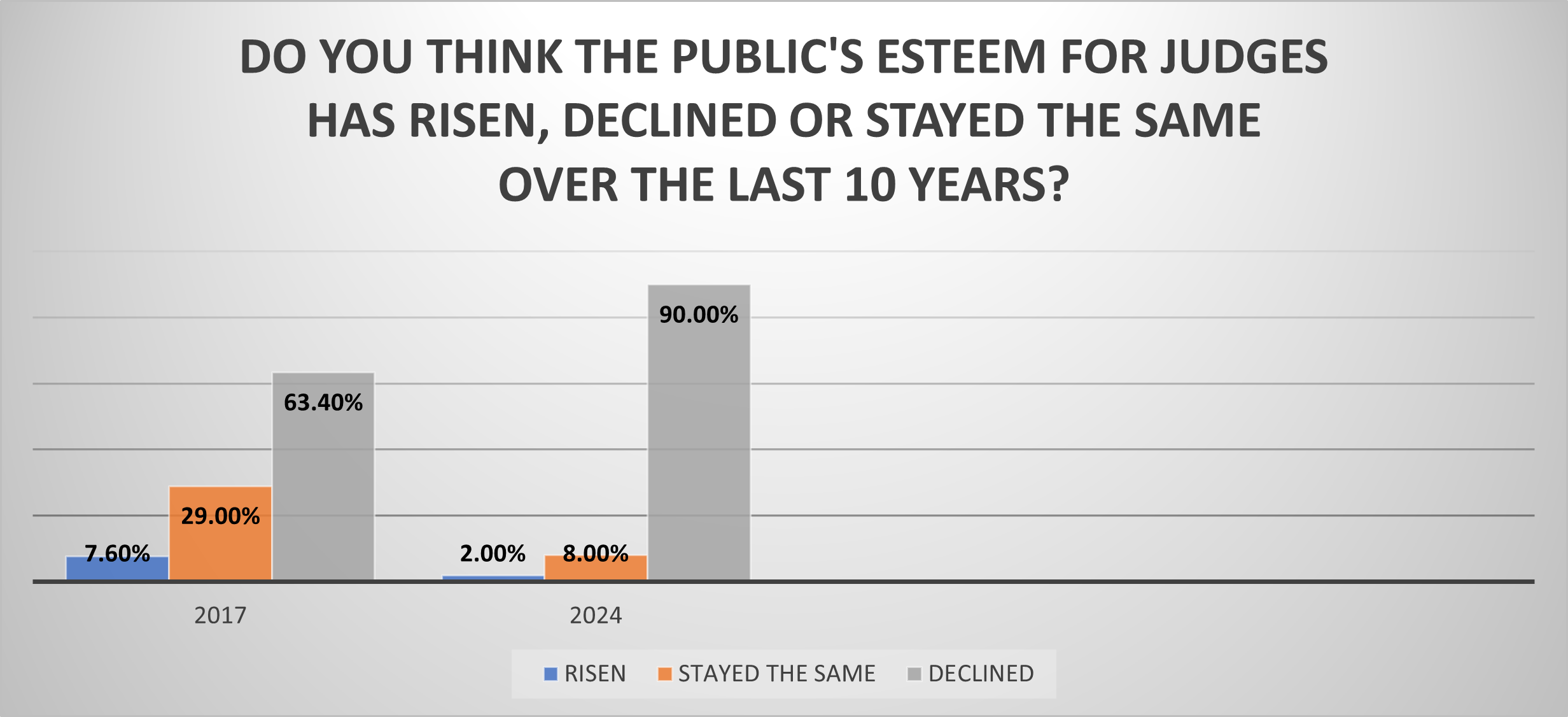

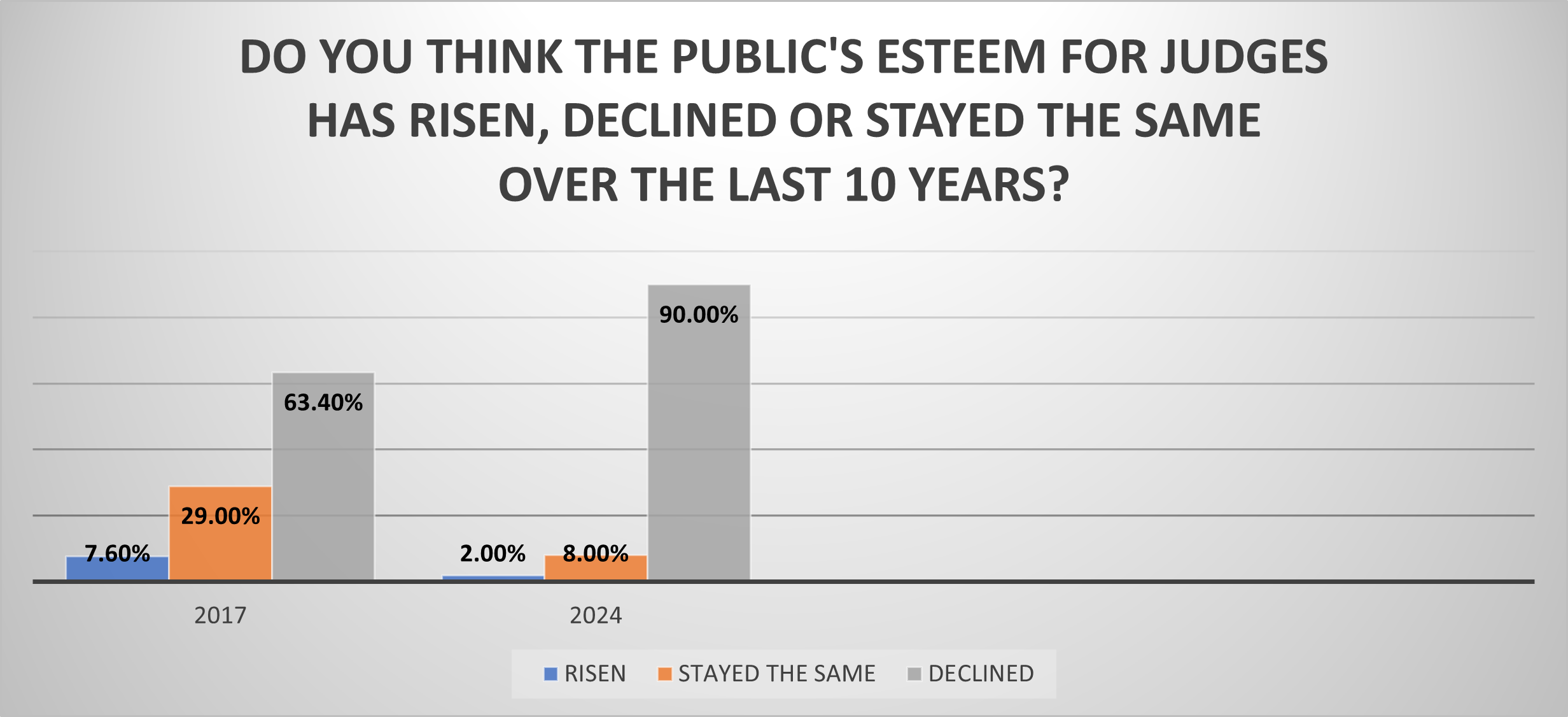

RENO, Nev. (March 8, 2024) — In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out...

In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out of 10 judges believe the publi...

RENO, Nev. (Jan. 26, 2024) — The nation’s oldest, largest and most widely attended school for judges �...