Prof. Douglas Lind

Ever since Justice Holmes asserted that “[t]he life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience,” lawyers and judges in the United States have minimized the importance of formal logic for understanding law and legal reasoning. Many legal scholars and practitioners have feared that to acknowledge that logic is central to law would risk a return to the rationalistic excesses of the formalistic jurisprudences that dominated nineteenth century legal thought. It was, after all, against that formalist tradition that Holmes wrote. And it was in spirited opposition to that tradition that members of the Legal Realist movement in America, as well as the Free Law movement in Europe, directed much of their energies early in the twentieth century.

[T]o comprehend is essentially to draw conclusions from an already accepted logical system.

Albert Einstein

There is good reason to remain skeptical of overly rationalistic accounts of law and judicial practice. The weave of historical doctrine, legal principle, and factual nuances that goes into each judicial decision is far too intricate to permit critical appraisal under any single evaluative method, including the principles of logic. So we are rightfully apprehensive when we recollect the formalistic visions of nineteenth century jurists — visions which found the essence of adjudication in the logical derivation of conclusions necessarily required by predetermined legal principles.

Yet it is somewhere between strict formalistic jurisprudence and an outright disregard for logic and argumentative form where the law and judicial practice really find repose. Though all that is typically repeated of Justice Holmes’ view is the pithy remark quoted above, his jurisprudential writings together with his judicial opinions show clearly that he never intended to suggest that logic is not a central aspect of law or judicial decision making. He, as well as the legal realists and other critics of legal formalism, well recognized that evaluating and creating arguments lie at the heart of the crafts of lawyering and judging.

It is thus worthwhile for practitioners and students of the law alike to possess an understanding of the basic principles of logic that are used regularly in legal reasoning and judicial decision making. This understanding requires, in important part, skill in navigating the processes of inductive reasoning — the methods of analogy and inductive generalization — by which inferences are drawn on the basis of past experience and empirical observation. The common law method of case law development, as well as the general prescript often referred to as “the Rule of Law” — that like cases be decided alike — are grounded logically in inductive reasoning.

Equally important is a second basic category of argumentation — deductive logic, especially the deductive argument forms known as “syllogisms.” These are the classic forms of deductive argument consisting of a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion. It was this aspect of logic that a century ago stirred such virulent opposition to formalism. And it is this aspect of logic which was so severely downplayed throughout the twentieth century. Yet even a rudimentary understanding of deductive logic gives lawyers, judges, and students of the law a valuable tool for determining whether an argument in a legal opinion or brief is valid or fallacious.

In essence, the domain of the law and, within that domain, perhaps most especially the practice of judicial decision making are exercises in practical reasoning. Law, to be sure, involves more than logic. Yet the myriad of factors that contribute to good lawyering and fair judging suggest that the “life of the law,” while not logic alone, is a manifold of activities that all use and depend upon reason in specialized ways. The precision of detail required in the drafting of contracts, wills, trusts, and other legal documents is a rational precision; the care in planning and strategizing demanded of trial attorneys in deciding how to present their cases is a rational care; the skill in written and oral argumentation required for appellate practice is, quite obviously, a rational skill; the talent expected of administrative law judges in crafting coherent findings of fact and conclusions of law is a rational talent; and the ability of trial and appellate court judges to separate, dispassionately and without bias, the kernel of argument from the rhetorical and emotive chaff of adversarial presentation, so as to render judgments that are justified under the law, is a rational ability.

While it is true that many other factors — from self-interest to moral values, from psychology to science — enter into the decision making of lawyers and judges, all such factors bear the ever-present tincture of reason and logic. Trial attorneys may appeal to the psychology or sentiments of the jury, but only so far as they reasonably expect to influence the jury to draw rational inferences in their client’s favor. Self-interest may be the sole driving motive for each party in the drafting of a contract, yet the recognition, grounded in reason, that insisting on onerous provisions will likely undermine the entire contractual arrangement has the tendency to hold everyone’s self-interest in check. And while adjudicative practice calls for a good deal of “value judgment” in the choice, interpretation, and application of legal principles, such value judgments are not free of the constraints of reason. As stated by one appellate court, “[E]very legal analysis should begin at the point of reason, continue along a path of logic and arrive at a fundamentally fair result.” (Sunrise Lumber v. Johnson, Appeal No. 165). To criticize, reverse, or overrule an administrative or judicial decision as “arbitrary,” “capricious,” “unsupported by law,” or “contrary to precedent” is to say nothing more, but nothing less, than that the decision is deficient in logic and reason.

This month’s one-question survey* of NJC alumni asked, “How is 2024 shaping up for you and your court?�...

RENO, NV (PNS) – As they eye their inaugural football season this fall, the Gaveliers have question marks...

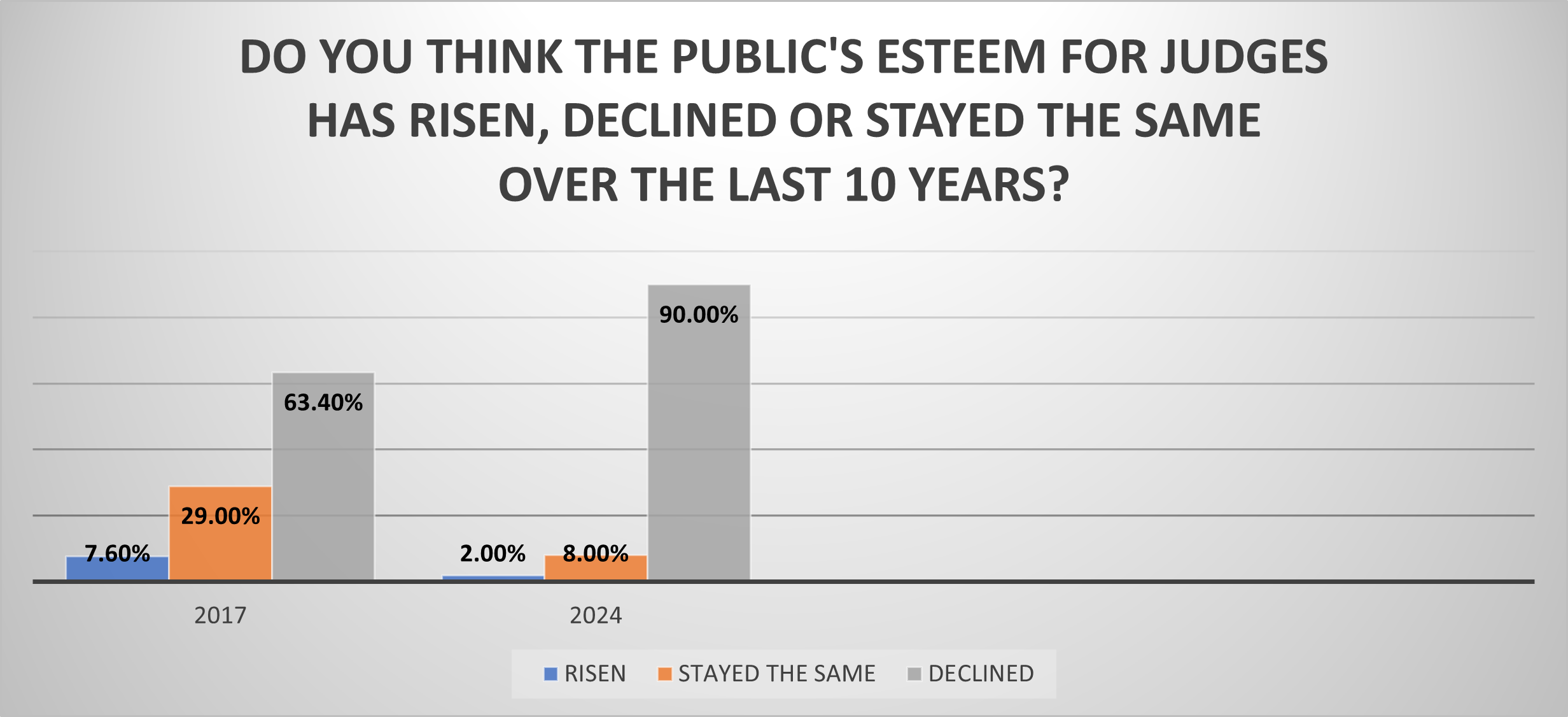

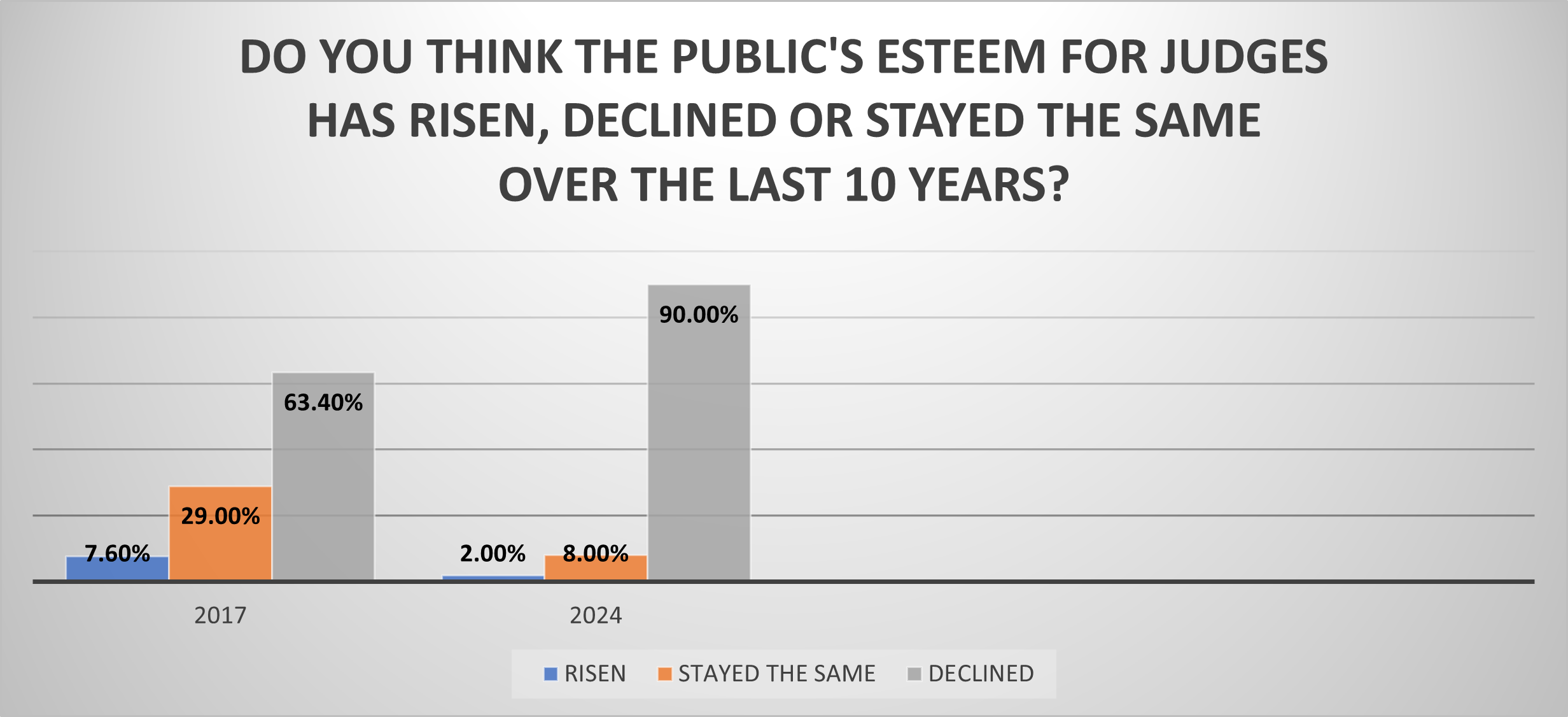

RENO, Nev. (March 8, 2024) — In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out...

In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out of 10 judges believe the publi...

RENO, Nev. (Jan. 26, 2024) — The nation’s oldest, largest and most widely attended school for judges �...