By Hon. David J. Dreyer

A few years ago, in the first two days after my state began recognizing same-sex marriages, I officiated over 50 such marriages. For reasons I did not expect, it changed my life.

Judges and lawyers are trained to think. But they also apply discretion, advocate, counsel, find solutions, and solve problems. Over and among all the things we do, there is always one large necessary intangible: connecting as human beings to others.

It is undeniable that we have to get along with our colleagues, clients and litigants. As professionals, we are, in fact, bound to do so. But we judges and lawyers share an even higher calling. We are stewards of the American system of justice. So we are obligated to ensure public trust in the law or else suffer public disorder.

We are the ones whose daily considerations include the public interest as well as the needs of private individuals. We represent unattractive clients, argue unpopular positions, and make reviled decisions because that’s what it takes to run a free society.

Because they carry the special burden of ensuring legal access for all, the careers of judges and lawyers, unlike any other jobs, are chock full of unique human beings. We see people who have fired employees, been hurt by their neighbors, fought with their business partners, hired the wrong guy to remodel their kitchen, been denied much-needed tax exemptions, were run over by a bus, or stole their children from a hated spouse.

Our professional skills will always include the ability to serve others, even when the “others” are disconnected from us. If we don’t do it, or can’t do it, the alternative is simply unacceptable. The system will only be a partial system, and that is no system at all. Our stock-in-trade is human relationships.

I have married more couples than I can remember over almost 38 years as a lawyer and judge. When a court decision allowed same-sex marriages in Indiana, the Marion County Clerk’s Office was deluged, so I just pitched in to help. I did not carry any flag for same-sex equality or gay rights. I did not publicly advocate one way or the other. But I know what I saw that day. It was uncommon and extraordinary.

I saw people who left their jobs to run downtown, get married, and rush back. They were the kind of people I have known all my life — ordinary people who get up every day, go to work, pay taxes, and turn this earth on its axis.

I saw people with gleeful children and beaming parents.

I saw people who have been together for decades.

I saw people who had exchanged rings (on their own) so long ago they couldn’t get them off to do it again.

I saw people of every means, walk of life, background and religion.

I saw a lot of very long hugs.

I saw several colleagues.

I saw a lot of tears.

At the end of a very long day and night, I felt more optimistic about human beings than I can ever remember feeling. That is something I did not expect. Before, all my marriage ceremonies united a man and a woman in their 20s or 30s. On that day, I united people literally of all adult ages. Two were in their 80s.

In the past, my happy couples had known each other a couple of years or so, it seemed. That week, the delirious couples had spent most of their adult lives together, some for as many as 30 or 40 years.

The people I married before were always hopeful it would last. The people I married that week already knew. As a practical matter, they had already been married a long time. For me, it was just all different.

As a judge, I knew that some of those new same-sex spouses would disappoint each other; people always do. But the weddings were so full of vitality and depth that a boundless optimism filled the entire City-County Building. I felt that even if the window of opportunity for same-sex marriage never opened again, those newlyweds wouldn’t care in the long run. I didn’t. What happened couldn’t be taken away.

Alexis de Tocqueville liked lawyers. He wrote that when “the American people are intoxicated by passion and carried away by the impetuosity of their ideas, it is checked and stopped by the almost invisible influence of its legal counselors.”

As a lawyer, I was privileged to be the legal, and invisible, part of these marriages, even if they would not last, or if other judges later would not recognize them. It was part of that privilege we lawyers and judges all share: connecting with literally anyone, especially when they really need you.

RENO, NV (PNS) – As they eye their inaugural football season this fall, the Gaveliers have question marks...

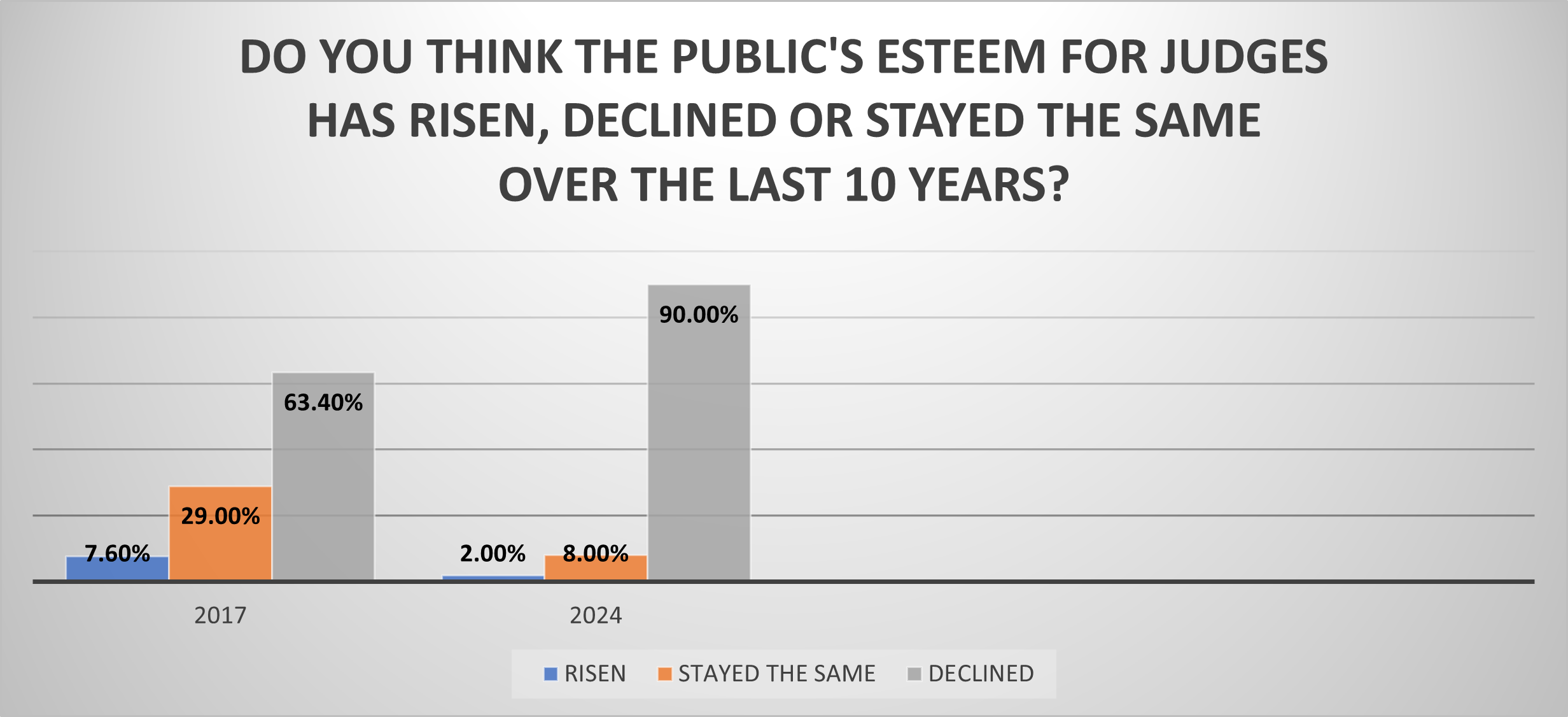

In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out of 10 judges believe the publi...

RENO, Nev. (Jan. 26, 2024) — The nation’s oldest, largest and most widely attended school for judges �...

RENO, Nev. (Feb. 7, 2024) — National Judicial College President & CEO Benes Z. Aldana received the Am...

It’s the bear, by a clear majority. A bear to be called Bearister. January’s Question of the Month* ...