By Prof. Steve Simon and Judge Mark Wernick

Judges and attorneys must have an “evidence ear.”

Trials are communication — using language and visual aids to elicit testimony from a witness via a question, to convince jurors or a judge of the proponent’s view of the case. For the attorney opposed to the question, the communication involves analyzing the admissibility of the answer called for by a question and articulating a proper objection.

A judge’s evidence ear requires understanding the rules of evidence, listening to a lawyer’s question in the context of previous questions, anticipating objections, and promptly analyzing the stated grounds in order to make a ruling.

In a hearing or trial, the challenge for the attorney who has the burden of proof is to ask questions that elicit from his or her witness, information that the attorney wants the fact finder to accept as true. With respect to each question, the challenges for the opposing attorney are to listen closely to the question, and then, before an answer is given, evaluate the admissibility of the possible answers to the question and, if necessary, object on proper grounds.

The challenge for a judge is to develop an evidence ear in order to quickly and accurately rule on objections. An attorney objects; the judge must decide. It is easier for an attorney to object than for a judge to decide.

Attending an Evidence in the Courtroom session gives judges the ability to develop an evidence ear in a trial simulation. This is done in two ways. First, hearing questions and objections in “real time” trains the judge to pay attention during the trial. Seldom should a judge ask an attorney to repeat a question; to do so implies that the judge was not paying attention.

Second, the “real time” simulation helps the judge obtain a practical, working knowledge of the rules of evidence. The rules of evidence are concepts written broadly enough to apply to a wide variety of recurring situations. It is only through applying those concepts to specific, trial-imbedded questions and answers that a judge can develop an evidence ear; the ability to quickly apply a general rule of evidence to specific instances of articulated questions, answers and objections.

Thus, applying the rules of evidence is best learned by experiencing their application in the courtroom; experiencing “evidence” just as judges and attorneys are exposed to it in the real world of a trial. The evidentiary, analytical process starts with a judge hearing a question and processing what he or she hears. The judge then hears an objection and must process and promptly act on the objection. These listening and intellectual skills are built on an understanding of the rules of evidence, listening to each question, analyzing the question for possible grounds for an objection, and then ruling on an objection if one is made.

The NJC offers the following evidence-related courses in 2105: Evidence in a Courtroom Setting (April 20-23 in Napa, CA), Advanced Evidence (May 18-21 in Reno, NV and August 10-13 in Big Sky, MT), and Evidence Challenges for Administrative Law Judges: A Web-Based Course (October 5-November 20).

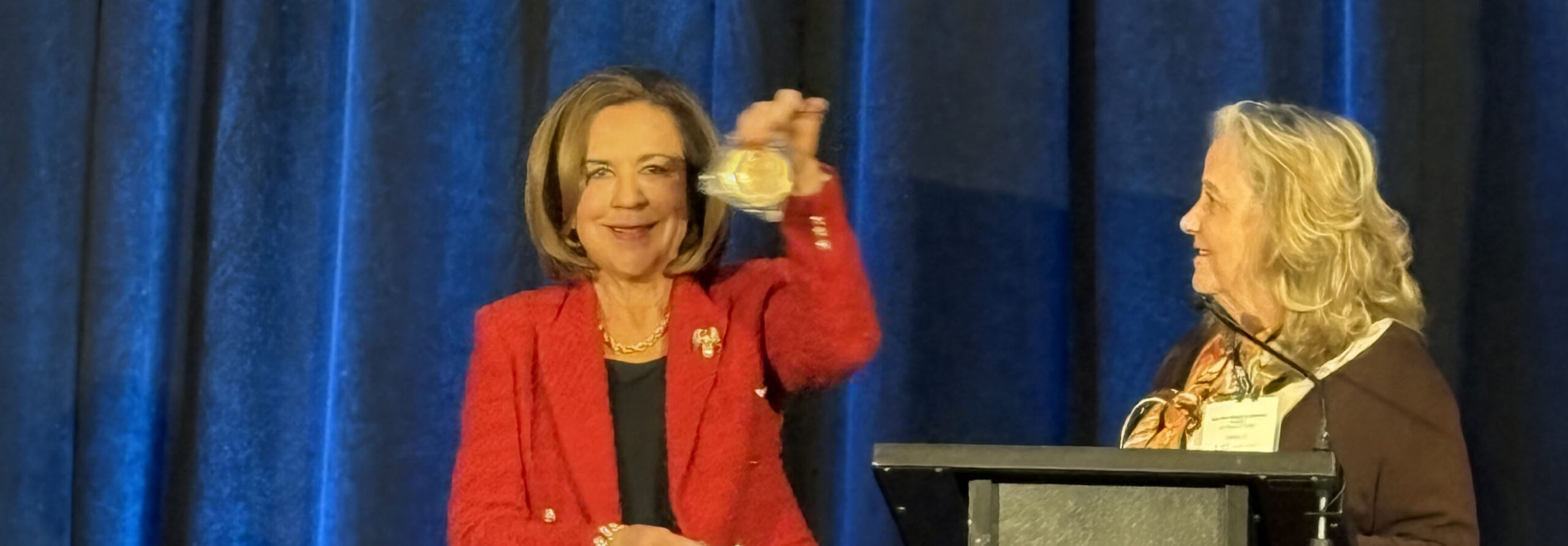

The National Judicial College has awarded Missouri Supreme Court Judge Mary Russell with the Sandra Day O�...

Emeritus Trustee Bill Neukom (left) with former Board of Trustee Chair Edward Blumberg (right) at the NJC 60...

The National Judicial College, the nation’s premier institution for judicial education, announced today t...

The National Judicial College (NJC) is mourning the loss of one of its most prestigious alumni, retired Uni...

As threats to judicial independence intensify across the country, the National Judicial College (NJC) today...