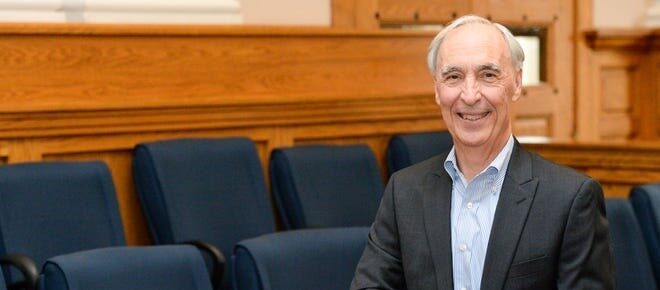

Lee Sinclair recalled that as a child he loved to visit the Stark County Courthouse in his hometown of Canton, Ohio. When he started law school, he made it his goal to become a judge.

He achieved that goal and so much more.

Retired Stark County Common Pleas Court Judge V. Lee Sinclair, a distinguished faculty member and former chair of the NJC Faculty Council, died April 30 after nearly four years of struggle against various cancers. He was 70.

Judge Sinclair served on the bench in Stark County from 1995 until his retirement in 2012. He taught his first class for the College in 2003 and his last (Mindfulness for Judges) online in August 2021.

He had a passion for teaching and didn’t limit his instruction to the NJC. Over the course of 30 years, he also taught for the Ohio Judicial College, Walsh College (now University) in North Canton, the National Center for State Courts, even the United States Army.

He was a pioneer and known nationally known for his work in raising awareness about judicial security. National media, including CNN, NBC, CBS, The New York Times and The Los Angeles Times, sought out his expertise, and he provided expert witness testimony in court security matters.

He was an especially engaging teacher. Longtime friend and co-presenter Timm Fautsko recalled a training they conducted together for Hawaii’s courts around 2010. The project took them to all five islands. Over the course of two weeks, they taught nearly 300 judges and other court personnel.

“He was amazing,” recalled Fautsko. “People loved the way he put his personality into his presentations…. He was so personable, so connective with people.” One of his secrets was his rich, deep voice. “He was a thespian at heart. In another life he would have been a Hollywood actor.”

During the Hawaii project and later courses, Judge Sinclair showed an 8-minute film on judicial security that he self-produced. Shot entirely in a courtroom, it dramatized common risks for violence. He titled it “John Gotme,” possibly a pun on mobster John Gotti. Before showing the film he would announce that they had spared no expense on the production, including casting Al Pacino in the role of the judge. It was actually Judge Sinclair, who kept his back to the camera.

Anyone who traveled with Judge Sinclair to teach would have noticed not only his meticulous preparation but his discipline of eating healthy and exercising regularly. In his younger days he had been a body builder. In later life, he left behind the bulging biceps but remained fit. He was also a master gardener and taught classes on gardening.

Until his cancer treatments became too much, he and his wife of nearly 28 years, Jan Sinclair, hiked all over the country and the world. For 20-some years they would visit East Yellowstone and watch generations of the same family of wolves live, hunt bison and die of old age. On another trip they walked to the bottom of the Grand Canyon and back – eight hours down, 12 hours up.

After law school, Judge Sinclair established a thriving career in private practice as a trial partner with Buckingham, Doolittle and Burroughs, one of Ohio’s largest law firms. He also served as Stark County Prosecuting Attorney.

In a 2012 essay for Stark County About magazine, he recalled that people tried to talk him out of giving up the salary and job security of his law practice to become a judge.

“It took me about two seconds to consider these concerns,” he wrote. “I decided to follow my dreams. I have never looked back, not once. The satisfaction of being a judge, of serving the community, so overshadows the money and security that I left behind.”

On the bench, Judge Sinclair was known as a fair and knowledgeable judge who listened and communicated well. He was tough on crime, particularly capital murder. He was the lead author of a two-volume treatise on “Handling Capital Cases” and was a contributing author to the leading judicial text on capital punishment, “Presiding Over a Capital Case.”

He seemed discouraged by certain trends in society, writing in the 2012 essay: “This is not the America we were 50 years ago. We have sat back passively and allowed at least two generations to grow up in an environment of no respect, no work ethic, a disdain for authority, and with no concept of right and wrong.”

But he seemed to take solace in his work to improve the judiciary. Jan Sinclair said her husband enjoyed teaching new judges coming onto the bench. And he was widely influential. She said she continues to gets calls from people looking for his advice, particularly on death-penalty cases.

Judge Sinclair knew that he faced a heightened risk of cancer. His daughter, Shannon Sinclair, an oncology nurse, told The Repository newspaper in Canton that her dad discovered he had inherited a mutation of the BRCA2 gene that makes men and women more susceptible to prostate or breast cancer. His mother died of breast cancer at age 42 when Lee was 15.

Of his work as a faculty member for the NJC, Jan Sinclair said, “He loved it. He just loved teaching and organizing the courses. It meant everything to him.”

The Hon. Leslie A. Hayashi (Ret.), a retired district court judge from the First Circuit in Honolulu, Hawai...

The National Judicial College has named Dean Aviva Abramovsky as its next president and chief executive off...

Ernest C. Friesen, Jr., the first dean of The National Judicial College, passed away on December 11, 2025, ...

The National Judicial College has awarded Missouri Supreme Court Judge Mary Russell with the Sandra Day O�...

Emeritus Trustee Bill Neukom (left) with former Board of Trustee Chair Edward Blumberg (right) at the NJC 60...