Note: To honor the memory of Judge Hora and with the encouragement of her friends and family, the College has established the Hon. Peggy Fulton Hora Scholarship Endowment Fund. Scholarships provided from this fund will enable judges from the United States and abroad to attend NJC courses. Contributions can be made by clicking here.

The College lost one of its finest teachers and the judiciary lost one of the original apostles of the problem-solving court movement with the recent passing of Hon. Peggy Fulton Hora (Ret.).

Judge Hora had been diagnosed with heart issues in recent years. She was in the process of receiving emergency treatment for an advanced internal infection when she suffered cardiac arrest and died on October 31. She was 74.

Judge Hora taught for the NJC more than 60 times over 27 years, as recently as last month. She received the College’s highest teaching honor, the V. Robert Payant Award for Teaching Excellence, in 2017, and was recently recognized as a Distinguished Faulty member.

“She was a force of nature and irreplaceable,” said NJC President Benes Aldana.

Hon. William “Bill” Schma, a friend for more than 20 years who worked with her in promoting therapeutic jurisprudence and drug courts, said her influence and achievements were comparable to those of the legendary and recently deceased Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

“She was deserving of that kind of description,” he said.

In 1992 Judge Hora chaired a committee that set up the second drug court in the United States, in her home state of California. She spent much of the rest of her life promoting problem-solving courts, which replace the conventional adversarial system with a collaborative approach that includes counseling. The goal is to solve underlying issues such as drug addiction that often lead to recidivism.

From the first drug court established in Miami in 1989, the problem-solving court movement has spawned specialty courts for veterans, mental health, domestic abuse, and homelessness, to name a few. Thousands of such courts have been created in the United States and abroad. Much of that growth can be attributed to Judge Hora’s tireless advocacy.

She promoted drug courts and other forms of therapeutic jurisprudence in Israel, the United Kingdom, Argentina, Chile, Bermuda, South Africa, Italy, Pakistan, France, Japan, Russia, The Netherlands and Canada. She was especially instrumental in establishing drug courts in New Zealand.

In 2009, the premier of South Australia appointed her a Thinker in Residence to study the Australian justice system and develop recommendations involving therapeutic jurisprudence and restorative justice.

Born in Oakland, California, Judge Hora got a late start in her legal career. In 2008, she told an interviewer, “I did everything backwards and nothing I should have done….”

After marrying young and having children followed by divorce, she attended community college and then California State University Hayward (now Cal State East Bay). After earning her law degree from the University of San Francisco, she worked as a staff attorney and later managing attorney with the Legal Aid Society of Alameda County, which includes Oakland. She handled mainly civil cases.

In 1984, as a 38-year-old legal aid lawyer with little trial experience, she made the unlikely decision to run for a local judgeship opening created by a retirement. She described the competition and the ensuing campaign as “three old guys scuffling among themselves and ignoring me altogether because they didn’t think I could pull it off. But I did.”

Assigned a criminal docket, she soon became dismayed at seeing the same offenders again and again, no matter how much she increased their sentences. Each time she admonished them to stop drinking or using drugs. But they didn’t.

She said she realized, “There is something different about these people that I am not understanding. And unless I’m going to engage in senseless acts for the next 20 years I need to figure it out.”

Her first step was to enroll in courses in chemical dependency, where she learned about brain chemistry and addiction. Around the same time the first drug court was established.

She sometimes likened the drug court approach to a Weight Watchers program in which people are urged to eat smaller amounts and must get on a scale periodically in front of people. In place of the scale, offenders had to turn in urine tests.

She helped found the National Association of Drug Court Professionals in 1994. In 1999 she co-authored a landmark article published in the Notre Dame Law Journal, “Therapeutic Jurisprudence and the Drug Treatment Court Movement: Revolutionizing the Criminal Justice System’s Response to Drug Abuse and Crime in America.”

In 2006 she retired from full-time service on the bench to devote more time to what she said she had become most passionate about: speaking, teaching and training all over the world.

Friends and collaborators in those efforts remember her always being impeccably prepared for her presentations. She expected the same of others.

“She always set high standards for all us in terms of the material we presented,” said Hon. Margarita Bernal (Ret.). The two met as instructors at the NJC in 1992, and Bernal is now a member of the College’s Board of Trustees. “She was like the informal dean of the teachers coming into Reno…. She expected excellence of herself and others.”

Longtime friend and colleague Hon. Brian MacKenzie (Ret.) said she had an unshakable commitment to ethics, and it wasn’t limited to judging and teaching.

“It went to small, everyday things like counting your change to make sure the person in the store didn’t give you back too much and then have that minimum-wage worker lose something from their paycheck,” he said. “She was committed to doing the right thing for the right reason at all times.”

Judge Hora was renowned for her encyclopedic knowledge on a wide range of subjects. Friends said she read not dozens but hundreds of books each year. She didn’t own a TV set for 30 years.

When she wasn’t reading, she was often writing. Her articles were cited more than 100 times by the appellate court and scholarly journals.

In 2015 when she was nearing age 70, she shifted gears from a life of public service to trying her hand as an entrepreneur and capitalist. Together with MacKenzie and David Wallace, an expert on highway safety and DUI issues, she founded the Justice Speakers Institute.

MacKenzie said the organization began as a simple bureau for scheduling speakers like themselves and has grown into a justice consulting firm. The group produced a landmark Science Bench Book for Judges for the NJC that Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer endorsed as a “helpful and necessary effort” for the judiciary.

She served as co-editor of the first edition and had just finished work on a second edition two weeks before her death.

Judge Hora’s intellect may have been rivaled in size only by her personality. Friends say she could light up a room with her smile and cheerfulness.

Schma, one of her co-authors on the famous Notre Dame Law Journal article, recalled meeting her for the first time in person at a reception during a conference. Up to that point they had only talked by phone, and he said he could feel her energy coming over the line.

“From way across the room, I heard this woman’s booming voice and a lot of laughter and excited chatter all around her,” he recalled. “There at the center of it was this woman wearing a blazing orange and red dress that stood out just like her personality. I could tell right away that it could only be Peggy Hora.”

She was a conversationalist with a sharp, ready and at least occasionally self-deprecating wit. Wallace, her co-founder of the Justice Speakers Institute, said she told him about a trial she judged that had dragged on for a long time. The defense counsel asked her for a continuance, and she said no. The lawyer replied, “Well it ain’t over until the fat lady sings.” She responded by singing in a high soprano, “OK. Guil-ty!”

She was an ardent but also playful feminist. Schma said one time she introduced him at a meeting of the National Association of Women Judges as someone who was “highly evolved for a male.”

“She was of the opinion that women were the superior species,” MacKenzie said. “I think she had a really good argument.”

Beyond problem-solving courts, her other great passions included food, movies, music, theater and her eight grandchildren. She often brought one or more of them along on her trips abroad. They called her “Venture Grandma.”

She was both an expert cook and a fan of great chefs and restaurants. She loved all foods, not just gourmet fare; ribs were a favorite. As with her professional work, she insisted on quality. Friends said if she wasn’t pleased by a dish, she would take one bite and leave the rest. If the wait staff offered a replacement, she would decline.

She was an early fan of the musical Hamilton and attended a dozen productions, friends said. That included one in Puerto Rico that featured the show’s creator, Lin-Manuel Miranda, who is of Puerto Rican descent.

Her Hamilton addiction eventually led to a performance of her own. At the retirement party for a fellow judge, she convinced MacKenzie and Schma to join her in a parody set to the signature rap from the show. They replaced “Alexander Hamilton” with the name of their retiring friend, Harvey J. Hoffman.

Mackenzie said, “It was just us three old white people. We planned it together. Harvey was really taken with it, even though he hadn’t heard any of the Hamilton lyrics before. We had a wonderful time. That was a moment.”

The Hon. Leslie A. Hayashi (Ret.), a retired district court judge from the First Circuit in Honolulu, Hawai...

The National Judicial College has named Dean Aviva Abramovsky as its next president and chief executive off...

Ernest C. Friesen, Jr., the first dean of The National Judicial College, passed away on December 11, 2025, ...

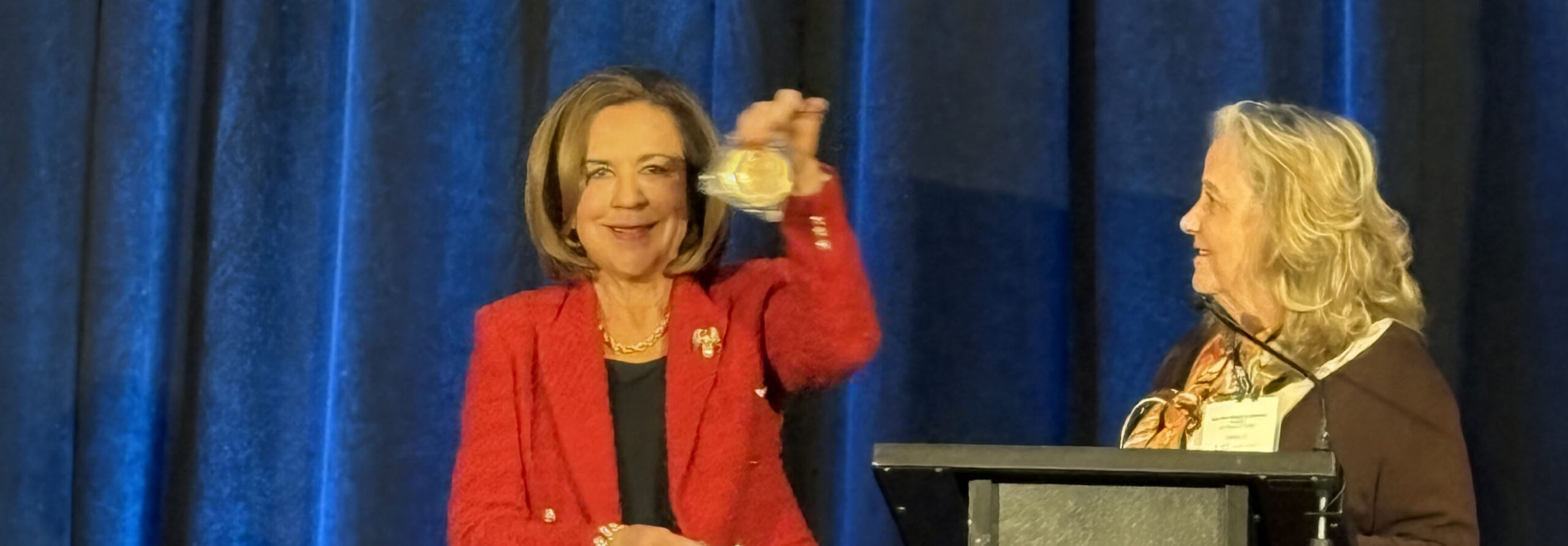

The National Judicial College has awarded Missouri Supreme Court Judge Mary Russell with the Sandra Day O�...

Emeritus Trustee Bill Neukom (left) with former Board of Trustee Chair Edward Blumberg (right) at the NJC 60...