By Hon. James M. Redwine

The United States Supreme Court has itself occasionally succumbed to

implicit bias and popular opinion then later attempted to atone for it.

The Dred Scott (1857) and Plessy v. Ferguson (1892) cases come to mind as examples of institutionalized injustice with the partial remedy of Brown v. Board of Education (1954) being administered many years later. In Dred Scott,

the Supreme Court decided that American Negroes had no rights that the

law was bound to protect as they were non-persons under the U.S.

Constitution. And in Plessy, the Court held that Mr. Plessy

could not legally ride in a “whites only” railroad car. The Court

declared that laws that merely create distinctions but not unequal

treatment based on race were constitutional. SEPARATE BUT EQUAL was

born.

Our original U.S. Constitution of 1787 disenfranchised women and recognized only three-fifths of every black and Native American person, and even that was only for census purposes. In my own state of Indiana, where I am a sitting Circuit Court trial judge, our Constitution of 1852 discouraged Negro migration to our state.

Were these documents penned by evil men? I think not. They were the result of learned biases and that omnipotent god of politics, compromise, which is often good but sometimes is not. As a judge I strongly encourage compromise in court, in appropriate cases. However, as one who grew up in a state where the compromise of the post-Civil War judges and politicians led to the legal segregation of schools, restaurants and public transportation, I can attest that some compromises simply foist the sins of the deal makers onto future generations.

When I was 6 years old, my 7-year-old brother, Philip, and I made our first bus trip to our father’s family in southern Oklahoma. We lived on the Osage Indian Nation in northeastern Oklahoma. It sounds exotic, but our hometown, Pawhuska, looked a lot like any town where I serve in rural Posey County, Indiana. In 1950, our parents did not have to worry about sending their children off with strangers except to admonish us not to bother anyone and to always mind our elders. When mom and dad took us to the MKT&O (Missouri, Kansas, Texas and Oklahoma) bus station it was hot that July day. Oklahoma in July is like most of America in July, but WITHOUT THE SHADE TREES!

My brother and I were thirsty, so we raced to the two porcelain water fountains in the shot gun building that was about 40 feet from north to south and 10 feet from east to west. Phil slid hard on the linoleum floor and beat me to the nearest fountain. And while I didn’t like losing the contest, since the other fountain was right next to the first one, I stepped to it.

“Jimmy, wait till your brother is finished. James Marion! I said wait!” Dad, of course, said nothing. He didn’t need to; we knew that whatever mom said was the law.

“Mom, I’m thirsty. Why can’t I get a drink from this one?”

“Son, look at that sign. It says ‘colored.’ Philip, quit just hanging on that fountain, let your brother up there.”

Of course, the next thing I wanted to do was use the restroom, so I turned toward the four that were crammed into the space for one. The signs read: “White Men,” “White Ladies,” “Colored Men” and “Colored Women.”

After mom inspected us and slicked down my cowlick again, we got on the bus, and I “took off a kiting” to the very back. I beat Phil, but there was a man already sitting on the only bench seat. I really wanted to lie down on that seat, but the man told me I had to go back up front. And as he was an adult, I followed his instructions.

Philip said, “You can’t sit back there. That’s for coloreds. That’s why that colored man said for you to go up front.”

That was the first time I noticed the man was different. That was, also, the point where the sadness in his eyes and restrained anger in his voice crept into my awareness.

And if all this seems as though it comes from a country far, far away and long, long ago, much of America segregated its black and white school children for almost 100 years after 600,000 men died in the Civil War. In fact, Brown v. The Topeka Board of Education was decided in 1954, and President Lyndon Johnson could not get the Civil Rights Act passed until 1964.

Whether we have learned from our history or are simply repeating it may depend upon whom we ask. Our Arab-American, Muslim, black, Native American, and Hispanic citizens, as well as several other “usual suspects,” may think the past is merely prologue.

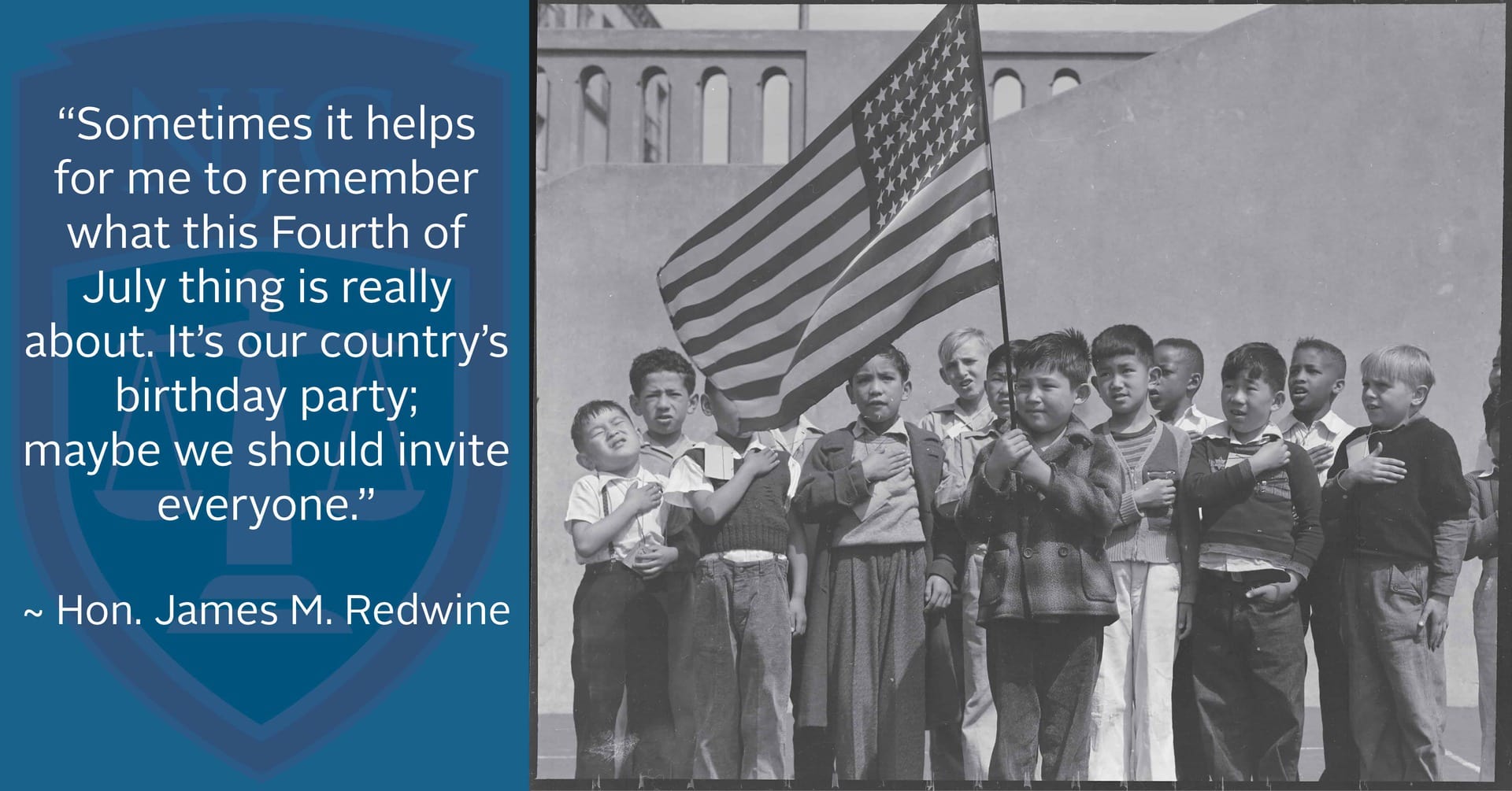

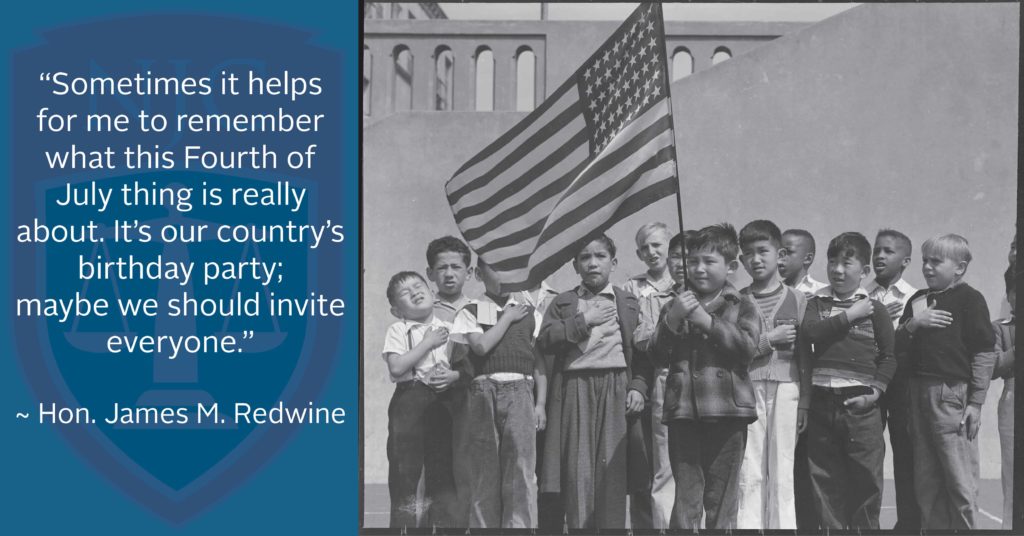

Sometimes it helps for me to remember what this Fourth of July thing is really about. It’s our country’s birthday party; maybe we should invite everyone.

There is nothing equal about separate.

Jim Redwine is retiring later this year after 38 years on the Circuit Court bench in rural Posey County, Indiana. An alumnus of the College many times over, he joined the faculty in 1998 and has taught hundreds of U.S. and foreign judges in this country, abroad and online. He specializes in libel/slander, trial skills, probate, criminal law and rural courts. He is the author of Judge Lynch! (2008) and a weekly newspaper column, “Gavel Gamut,” collected into the anthology Gavel Gamut Greetings from JPeg Ranch (2009).

CHICAGO – The American Bar Association Judicial Division announced recently that TheNational Ju...

The National Judicial College is mourning the loss of former faculty member Judge Duane Harves, who passed ...

As the world manages an evolving natural environment, The National Judicial College announced today that it...

Do’s Manage your cases systematically Devise a system that works for you and your organizational...

After 22 years of teaching judges, Tennessee Senior Judge Don Ash will retire as a regular faculty member a...