Abby Abinanti remembers it as a particularly big fight.

Two men in her Yurok tribe were engaged in a dispute about a haul of fish from the Klamath River in far Northern California. The Yurok Indian Reservation straddles the river.

She summoned the pair to her court and issued a restraining order because, as she put it to them bluntly, “If you two knuckleheads kill each other, I can’t fix that.”

There does not appear to be much Abby Abinanti cannot fix, and in the case of the quarrelsome fishermen, her solution was classic tribal justice. She told the men they should have known what to do – go to one of the tribe’s Dance Leaders and ask for their help in resolving the dispute.

“I happen to have one here today with me,” she mentioned dryly. “If you want to talk with him I’ll let you go outside and talk. And if you don’t resolve it there and come back in here, you’re going to face one mad old Yurok woman. So be very careful.”

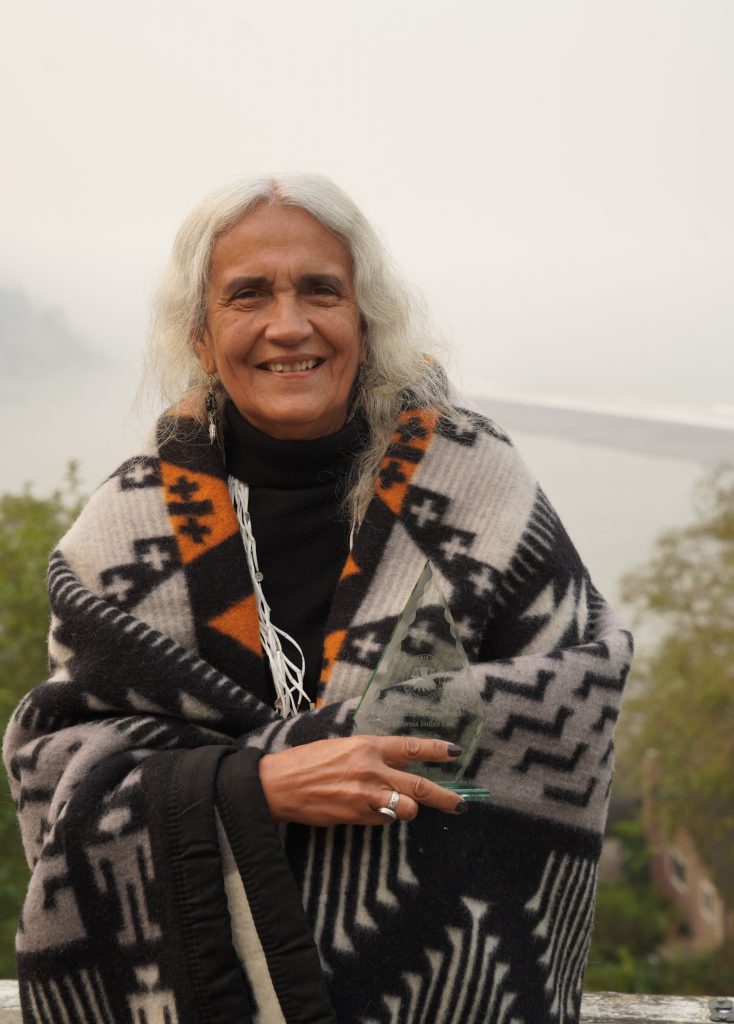

Abby Abinanti, 73, is not only one of the feistier judges you’ll meet, she’s one of the country’s most prominent, vocal, successful and influential tribal judges. In 2020 the Indian Law Section of the Federal Bar Association recognized her with its Lawrence R. Baca Lifetime Achievement Award.

The documentary “Tribal Justice,” which debuted on the long-running PBS series POV in 2017, brought her to the attention of a wider audience. The film follows the efforts of her and a judge with another tribe as they endeavor to dispense justice based on traditional Native values.

That means far less emphasis on individual rights and punishment and far more on restorative justice, making the community whole, living in harmony. That includes coexisting with the natural world. The Yurok, for instance, have strict rules against polluting or overfishing the Klamath.

“Judge Abby,” as she is widely known in Indian County, was born in San Francisco but grew up in Humboldt County near the Yurok reservation. After studying journalism at nearby Humboldt State University, she went on to law school because, as she puts it, “Three old ladies ganged up on me.”

The women were Yurok elders who took her for coffee one day as she was nearing college graduation. They mentioned a scholarship available to her to attend law school.

“I said, ‘I don’t want to go to law school,’ and they said, ‘Too bad, you’re the only one graduating, so you’re going.’ I said, ‘No, I’m not.’ But you can’t win fights with them.”

In 1974 she became the first female Native American admitted to the State Bar of California. In 1994 she was appointed a commissioner of the San Francisco Superior Court. Court commissioners are judicial officers who preside over cases that are assigned by statute. As such she became the first California tribal person to serve as a judicial officer of the state.

During her 17-year career with the Superior Court she worked out of United Family Law Division, handling mostly juvenile dependency and delinquency cases. She showed that she would not hesitate to make waves when it came to the welfare of children.

She recalled the case of an 11-year-old boy who had gotten into a fight in the schoolyard. He ended up spending the weekend in jail and then the prosecution wanted to charge the child with serious offenses. She was astonished. No weapon had been involved.

She remembers telling the prosecutor, “I don’t know what you’re thinking, but this is not going to work. If a kid isn’t old enough or tall enough to ride the tea cup ride at Disneyland, he’s not getting a criminal conviction for a schoolyard fight.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, she held judicial appointments with the Hoopa Valley, Colorado River, Shoshone-Bannock and Hopi people. She has been chief judge of the Yurok since 2007.

She said she’s glad to be back home and spending the last part of her career building up what she sees as an infrastructure consistent with her people’s belief system.

“With the state system or the federal system, you have all these rights. You have a right to remain silent. You have a right to this or that. Here it’s really about responsibility and if you’ve made a mistake how are you going to fix it.”

She mentions the case of a couple of boys, cousins, who broke a rule about how long fishing nets could remain in the river. One had a reasonable excuse, the other had just been careless. She told the culpable cousin that he could either pay the fine, which amounted to several hundred dollars, or she could give him his net back if he promised to bring fish to the traditional dance that weekend. He took the deal.

“Then he said, ‘How will you know if I did it?’ I said, ‘Because I will be at the dance, and if you don’t do it, you’re going to have a really bad Monday morning. He said, ‘Oh, I was going to do it, I was just wondering.”

The memory makes her laugh.

Speaking of laughing, and dancing, the “two knuckleheads” with the fishing dispute also took her up on her restorative justice offer and met with the Dance Leader. About an hour and a half later, she said, they returned to her office laughing and talking. They told her not to worry, they had fixed the problem.

“I said, ‘That works for me. Now go home and tell your sons and your grandsons how you resolved this and then we’re done.’”

CHICAGO – The American Bar Association Judicial Division announced recently that TheNational Ju...

The National Judicial College is mourning the loss of former faculty member Judge Duane Harves, who passed ...

As the world manages an evolving natural environment, The National Judicial College announced today that it...

Do’s Manage your cases systematically Devise a system that works for you and your organizational...

After 22 years of teaching judges, Tennessee Senior Judge Don Ash will retire as a regular faculty member a...