By Hon. Jan W. Morris (Ret.)

Earlier this month, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the treaty-established Muscogee (Creek) reservation in Oklahoma – which together with four other tribes’ reservations spans nearly half the state – was never disestablished by Congress, so it remains “Indian country” for the purposes of federal Major Crimes Act prosecutions. However, the Court’s opinion, which came in the case of McGirt v. Oklahoma, isn’t the earthshattering usurpation of states’ rights that some folks (including the dissent) seem to perceive.

True, the governmental sovereignty interests of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and potentially other indigenous tribal nations, which were (unfortunately) aligned with the due-process interests of a convicted sex offender, Seminole Nation member Jimcy McGirt, were preserved. That is as it should be. In an extraordinarily rare “win” for tribal self-governance in the opulent marble- and mahogany-clad shrine to the American Rule of Law, an Indian tribe’s interests were recognized and confirmed, even if collaterally so.

Justice Gorsuch, whose knowledge, understanding and appreciation for tribal sovereignty and self-government stems from his extensive 10th Circuit Indian law jurisprudence, authored the Court’s opinion that “hold[s] the government to its word.”

This brings to mind the thoughts of Lakota leader Red Cloud, who is reported to have said, “They made us many promises, more than I can remember. But they kept but one — They promised to take our land … and they took it.”

‘The government of such Indians’

International treaties are recognized among the trilogy of sources that constitute the “supreme law of the land” under the U.S. Constitution. European nations, as well as some of the English colonies in America, and later the government of the United States of America historically recognized the sovereignty of tribal nations in North America and willingly entered into treaties with tribal nations with three primary goals: for trade and to ensure a peaceful coexistence of indigenous and immigrant neighbors; for land cessions to provide for “American” population growth and natural resources acquisition; and to engender exclusive tribal fidelity to the United States by promising the protection of the fledgling American government against foreign nations who might seek to take advantage of, or even decimate, the tribes (the latter being a disingenuous veil to convince tribes not to join European nations in war against the United States).

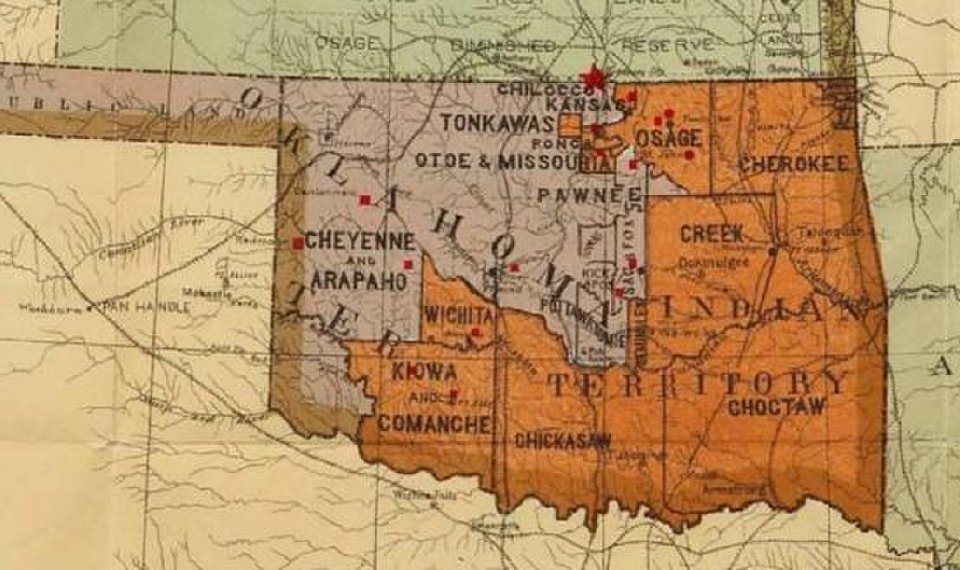

Through a series of treaties with the Creek Nation in the 1830s, the United States encouraged the Creeks to cede their communal use, occupancy and all other interests in their traditional ancestral lands in Georgia and Alabama to the United States in exchange for the establishment of the “Creek country west of the Mississippi [that] shall be solemnly guarantied to the Creek Indians” as a “permanent home” located in what is now Oklahoma where “[no] State or Territory [shall] ever have a right to pass laws for the government of such Indians, but they shall be allowed to govern themselves.”

Thus, the Creek reservation was established by Congress upon the ratification of the treaties. Conversely, it also takes an act of Congress to disestablish an Indian reservation that Congress has previously created. The upshot of McGirt is that Congress must explicitly express its intent to disestablish a congressionally created Indian reservation, which it did in numerous situations identified by the Court involving treaties with various other tribes.

Given these examples, it is clear that Congress knows how to disestablish an Indian reservation and evince its intention to do so. However, in the case of the Muscogee (Creek) reservation, while it took several steps to diminish the reservation, Congress did not expressly disestablish it.

As a result, the area within the exterior boundaries of the original Creek reservation in Oklahoma remains “Indian country” for Major Crimes Act purposes, thus precluding the State of Oklahoma from exercising criminal jurisdiction over certain crimes allegedly perpetrated by Native Americans which crimes occur within the boundaries of the original Muscogee (Creek) reservation.

Only the federal government, concurrently with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, can prosecute in that instance, to the exclusion of the state. That is how the McGirt decision tangentially qualifies as a win for tribal sovereignty. As a former tribal judge, I appreciate that distinction.

Magic words

In its briefing and argument, Oklahoma pointed to its “long historical prosecutorial practice of asserting jurisdiction over Indians in state court, even for serious crimes on the contested lands. If the Creek lands really were part of a reservation … all of these cases should have been tried in federal court pursuant to the MCA.”

Yet, until the Tenth Circuit’s Murphy decision a couple of years ago, no court embraced that possibility. The dissent contends that the historical reality of prior Supreme Court decisions that found Indian reservation disestablishment purportedly using less-than-explicit language or methods, combined with state and federal historical practice, should carry the day and that there should be no “magic words” that Congress must use to disestablish an Indian reservation.

But the concept of express and unequivocal language is not new. As I see it, the same principle was upheld nearly 50 years ago with regard to tribal sovereign immunity from suit. For 10 years after enactment, the practice was for various federal courts to entertain numerous lawsuits against tribal governments for alleged violations of the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968. Then, in 1978, the Supreme Court decided Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez in which the Court stated that, despite historical practice to the contrary, when Congress enacted the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968, it did not evince its intention to waive tribal sovereign immunity [except via habeas corpus pursuant to § 1303] which waiver must be “unequivocally expressed.” With regard to relying on historical practice rather than unequivocal expression to disestablish an Indian reservation, Gorsuch and the majority said, “[w]e must reject that thinking. If Congress wishes to withdraw its promises, it must say so.”

Native thinking is often holistic. We don’t always see individual events as unrelated phenomena. Native thinking is about relationships, that is, how everything relates to everything else, whether it be the natural world or human interaction or spiritual belief.

For this reason, Native Americans may view the McGirt decision against a backdrop of formal American-Tribal Nation relations. History is replete with the big-picture pendulum of U.S.-tribal relations, swinging back and forth over the decades and centuries. Over the past 230+ years the federal policy has oscillated from extermination to assimilation to termination to self-determination. If one views the establishment of lands set aside for the exclusive use and occupancy of indigenous inhabitants “for as long as the grass grows and the water flows” as an example of self-determination, some treaty-making comports with that policy, as does the enactment of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 and the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975.

Interspersed between those events were federal policies to force assimilation of Native people (who generally didn’t want to become “civilized” and who only ever wanted to be left alone) into the “dominant society” or to simply legislate their demise as governmental sovereigns.

Assimilation was attempted via land allotment (e.g. the General Allotment Act of the 1870s, which in theory was designed to force Natives with a history and culture of communal land stewardship to adopt the concept of individual land ownership where, despite their sometimes historic culture of hunting/gathering, they would learn agricultural arts and thus become “civilized” like their White patrons), and mandatory attendance in federally created or sanctioned faith-based boarding schools beginning in the late 1890s (“kill the Indian, save the child”).

Allotment was also intended to eliminate communal tribal land and hold the allotted land in trust until, after a period of years, the land would magically convert to fee land and its holder would be a full American citizen. After the requisite period, the new fee land would be subject to state and county taxes, which impoverished Natives didn’t understand and couldn’t pay and the land would be sold to non-Natives on the cheap for back taxes, eliminating both the tribal culture and the tribal land base, effectively terminating the tribe’s existence.

The ruinous “Relocation” programs of the 1950s similarly sought to remove Natives from tribal communities by sending them to major urban areas, where they could purportedly learn employment skills and become part of “American society” far away from their home, their people and their culture. Relocation fit neatly into both assimilation and termination policies. Legislation that directed tribal government termination was the policy of Congress in the early 1900s and the late 1950s and resulted in over 100 previously recognized tribes simply ceasing to exist because Congress said so.

Preface to the apocalypse?

When, from a Native perspective, McGirt is considered as a part of this continuum, it’s plain to see why tribes and their members may celebrate the decision. It moves things a little closer to restoring the original harmony of the Native world. Land that was promised and given to the Creek Nation “in perpetuity” remains under the stewardship of the Creek Nation. It’s comforting to me as a Choctaw citizen to know that Oklahoma must recognize my Grandad’s allotment in Haskell County, Oklahoma, now held by my cousin, as a part of the Choctaw Nation.

McGirt is not the preface to the apocalypse for the State of Oklahoma or its non-Native citizens. It doesn’t restore title to the land back to the Muscogee (Creek) Nation since that was not the issue before the Supreme Court. It does, however, confirm that, because the reservation still exists as Indian country, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation should continue to exercise its sovereign responsibility to be responsive to the public safety needs of its citizens and all Native Americans within its territory.

This case was about one tribe and one Native wrongdoer and addressed only the issue of which polity possessed authority to hold that wrongdoer accountable.

We cannot foretell what subsequent national impact this decision may have on other diminished reservations around the country, or in PL 280 states, or on other criminal justice issues, or on collateral civil and regulatory matters. What can be hoped for is increased recognition by both federal and state governments of the current and historic political status, governmental authority, and sovereign responsibilities of tribal nations within their territories.

The July 16, 2020, “Murphy/McGirt Agreement-in-Principle” between Oklahoma and the Five Tribes showed early promise, but even some of the Five Tribes do not believe it goes far enough.

Whether we’re talking about criminal jurisdiction or Covid-19 highway checkpoints, let’s get past the “us-against-them” mentality. Mutual respect of governmental authority and sovereignty should be the cornerstone of federal-tribal-state relations concomitant with the federal government’s espoused policy of a government-to-government relationship with sovereign tribal nations.

CHICAGO – The American Bar Association Judicial Division announced recently that TheNational Ju...

The National Judicial College is mourning the loss of former faculty member Judge Duane Harves, who passed ...

As the world manages an evolving natural environment, The National Judicial College announced today that it...

Do’s Manage your cases systematically Devise a system that works for you and your organizational...

After 22 years of teaching judges, Tennessee Senior Judge Don Ash will retire as a regular faculty member a...