By Hon. Ben A. Fuller

Hon. Ben A. Fuller

Most scholars agree that the development of American law is generally a reflection of our aspirations and the evolving assumptions we have about our culture, society, and political institutions. Examining the evolving, and, often transitory, nature of our ideas of justice, fairness, and equity can provide a brief glance at our path through history and a snapshot of the important issues addressed during particular periods in our legal evolution.

Perhaps, more importantly, we may sense the direction of American law and how our children and their children will address the complex and unprecedented issues that will face them over the next 100 years.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes once remarked, “The life of the law has not been logic. It has been experience.” The American legal experience has been one of general success but, at the same time, one marred at times by an apparent disconnection from our aspirations. The truth, however, is this: In evaluating our path of justice and reflecting on our successes and failures, we must be mindful that men and women of good faith, seeking honestly to find solutions to difficult and immediate problems, have viewed those problems, and their contemporary world, through the only eyes they had, their own. A study of the history of our professional thought allows us to borrow, if only partially, the eyes of those who have undertaken our work during difficult periods and under challenging circumstances.

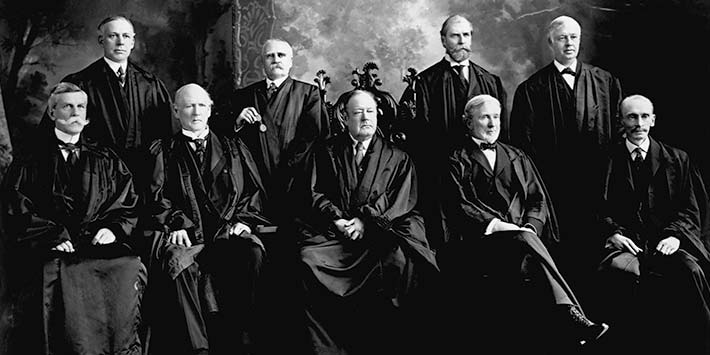

I am occasionally reminded that a striking number of past decisions of the United States Supreme Court are, when viewed from a modern perspective, almost universally considered to have been wrongly decided. Now, to be sure, we can disagree about the correctness of that Court’s decisions in a number of cases that are decided each term. After all, disagreement about a particular issue has commenced and has sustained any case that the Court ultimately resolves. Whether we agree or disagree, generally a reasonable argument can be made supporting or opposing the outcome of a particular controversy.

A survey of the past 225 years of Supreme Court jurisprudence reveals a number of decisions that I consider to be in, or at least approaching, a category that we might respectfully refer to as “regrettable decisions.” While you may have a list entirely different, I offer several cases generally considered today to be in the “regrettable” category.

“Regrettable Decisions”

The first, considered by many to epitomize the term “regrettable decision,” is Dred Scott v. Sanford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857). You will recall that in Dred Scott the Supreme Court held, inter alia, that African-Americans, whether free or slave, were not and could not be considered citizens of the United States or of any State within the United States. Enough said about that. In Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905), the Court, then applying a high degree of protection to contracts, business interests, and industry, overturned a New York statute that, in attempting to protect bakers, imposed a 10-hour limit on the time bakery employees could be required to work each day. In doing so, it identified an implicit “liberty of contract” protection ostensibly found within the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment and, in so doing, gave us what has come to be identified pejoratively as the Lochner era.

Later, during a period of intense interest in the science or pseudoscience of negative eugenics, a subject of particular interest and a favorite of Adolph Hitler, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, considered by many to be the Oracle of the Supreme Court, considered a challenge to a Virginia statute permitting compulsory sterilization of the “unfit.” Writing for the Court’s majority in Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927), Justice Holmes upheld the forced sterilization of individuals suffering from intellectual disabilities for the extolled purpose of “protection and health of the state.” In so doing, Justice Holmes wrote, “Society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind”. He ended the opinion by gratuitously declaring that “three generations of imbeciles are enough.” The Supreme Court has never expressly overturned that decision, but Virginia’s sterilization statute was finally repealed in 1974.

With World War II on the horizon, Justice Felix Frankfurter, writing for the Court’s majority in Minersville School District v. Gobitis, 310 U.S. 586 (1940), decided that public schools could, on threat of expulsion, compel elementary students to salute the flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance, despite their sincerely held religious objections to the practices. Mercifully, a reversal of that decision followed three years later when Justice Robert Jackson, writing for the Court’s majority, explicitly rejected the holding in Gobitis and delivered an inspiring defense of the fundamental rights of Americans:

If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein. If there are any circumstances which permit an exception, they do not now occur to us.

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943).

Finally, Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) and Korematsu v. United States, 324 U.S. 885 (1944) stand as examples of a judicially jaundiced view of the principles of fairness, justice, and, as is obvious in the two opinions, equality. The Court’s infamous “separate but equal” ruling in Plessy upheld state segregation laws and, in so doing, ensured that the hard-fought rights achieved by African-Americans during the post-Civil War Reconstruction era would be replaced by decades of entrenchment and subjugation of those rights under the infamous Jim Crow laws. In Korematsu, the Supreme Court upheld the internment of over 70,000 Japanese-Americans (better termed “Americans”) during World War II, after concluding, based upon what has now been determined to have been false and misleading evidence, that the nation’s need for protection from possible acts of espionage outweighed the individual rights of these particular American citizens.

How History Can Help Today’s Judge

So, why would a busy judge with limited time and resources be interested in examining or reexamining the history and development of American jurisprudence? The answer is simple and obvious. The maturing of American society and the continued development of our collective views and notions of fairness and equality, announced through our highest institution of justice, are evolving and, at times, elusive processes. The plain fact is that the billows of mist, the fog, and the thickets that blur our human perception, together with our notions of what is orthodox during a particular moment in time, may cloud our ability to correctly judge highly contentious and controversial issues because our judgments are made in the present, or, in the modern vernacular, “real time.”

Experience and, indeed, caution, reminds us that Judges, during past generations, have viewed complex and vexing issues of law not through the eyes of a 21st Century jurist but, rather, through the only eyes they had. Modern attitudes as to the righteousness or morality of a particular decision may be debated, but, in fairness, must be viewed within the context of the times during which the case was decided, together with at least some degree of confidence that the decision was reached in good faith, by honest judges applying the rule of law as they understood it, at that particular time in our history and under the influence of the social norms, attitudes, customs, political environment and the particularized needs of their generation’s society. We may then acknowledge that in so doing, those judges at times, reached conclusions that, when examined in the light of contemporary standards, fall shockingly short of the modern American’s notion of justice.

But there is good news. With modest effort and glancing reflection, we can benefit from the delightful perspective of hindsight and from the experience of our professional forebears. There can be little doubt that future generations of Americans will stand in judgment of our decisions. In so doing, they will, in all likelihood, add to that list of regrettable decisions that fall short of the ideals to which we virtuously aspire. But, as inevitable as their future list may be, I believe we can mitigate its length, at least to some degree, by pausing to thoughtfully reflect on our past efforts to establish and maintain justice and equality and by candidly evaluating our past failures. We may then continue in our work, confident that, just as the regrettable decision in Gobitis laid a foundation for the magnificent and inspiring discourse of Justice Jackson three years later in Barnette, our failures and shortcomings can provide a meaningful foundation for future success as we continue to strive toward our common goal, the highest attainable levels of fairness, justice, and equality.

Judge Fuller will teach the NJC’s course Today’s Justice: The Historical Bases in Philadelphia on Sept. 19-22.

CHICAGO – The American Bar Association Judicial Division announced recently that TheNational Ju...

The National Judicial College is mourning the loss of former faculty member Judge Duane Harves, who passed ...

As the world manages an evolving natural environment, The National Judicial College announced today that it...

Do’s Manage your cases systematically Devise a system that works for you and your organizational...

After 22 years of teaching judges, Tennessee Senior Judge Don Ash will retire as a regular faculty member a...